NORTH SAILS BLOG

All

Events

Guides

News

People

Podcast

Sustainability

Tech & Innovation

Travel & Adventure

OFF-SEASON AND WINTER SAIL CARE GUIDE

North Sails Service Expert, Ben Fletcher shares his top tips on how to protect and care for your sails in the off-season.

READ MORE

READ MORE

FOUR KEY COMPONENTS TO OFF-SEASON SAIL CARE

The off-season is the ideal time to give your sails the TLC they deserve. Keeping your sails on an annual maintenance schedule will aid in extending the lifespan of your sails and maintaining peak performance.

READ MORE

READ MORE

OFFSHORE SAILING GUIDE

When venturing offshore, there are numerous considerations to ensure a safe and successful journey to the finish line.

READ MORE

READ MORE

HOW TO CARE FOR YOUR FOUL WEATHER GEAR

Nigel Musto, North Sails Performance Clothing Director, gives us his top tips on maximizing the life of Foul Weather gear.

READ MORE

READ MORE

FLYING SAILS 101

North Sails President and world-renowned race winner Ken Read lends his expertise to our Flying Sails Guide, a new breed of offwind sails that can add as much as 40 percent more sail area.

READ MORE

READ MORE

CAPE 31 TUNING GUIDE

The Engine Above Deck

The North Sails team has focussed hard on the Cape 31 Class since its inception and as a result it is no surprise that North Sails have been so dominant. North Sails IRC designs were the foundation of the Cape 31 One design rules. Starting as the sole sail maker in South Africa with tri-radial paneled, North Sails have worked to perfect their 3Di sails since the Cape 31 arrived in the UK in 2019.

After countless hours sailing, testing and competing in the Cape 31, North Sails shares our tuning notes in an effort to get sailors and teams up to race winning speed quickly for the most competitive racing. As we learn more about the Cape 31 and further its development, new information regarding setup, tuning and trimming techniques will be updated online at northsails.com. As always, contact your North Sails Expert for all the most up to date information and for help tuning your boat.

Tuning Guide

Dock tune

Mast heel position: 135-145 mm from the aft edge of the mast to the center of the front keel bolt. Set the mast heel position to achieve the desired pre bend (see below). Moving the heel aft increases pre bend, moving the heel forward reduces pre bend.

Setting the mast rake: 1,710mm. To do this, put a mark on the forestay, and measure the distance from this mark down to the middle of the forestay pin at the deck intersection.

Swing the fixed end of the jib halyard back to the mast and mark the halyard in line with the top of the gooseneck measurement band.

Next swing the jib halyard forward to the forestay and mark the forestay in line with the jib halyard mark.

Measure the distance from the top of this new forestay mark to the middle of the forestay pin. On most boats this is the load sensor pin, the pin that the tack of the jib attaches to.

The next step for tuning the rig is to make sure the mast is square in the boat.

Set the shroud tension close to base tension and loosen the D1’s (& D2’s).

Swing the jib halyard from one shroud base to the other and make sure the hounds are in the middle.

Tighten the D1’s (& D2’s) back up to the tuning guide and make the mast look straight side to side.

Base deck chocks: It is best to have light pressure on the front chocks. A good base deck chock setting is normally 4 to 8 mm of positive chock (fill the gap in front of the mast, plus 4-8mm). It is worth checking that when on +1 chocks compared to base that there is still a small amount of pre bend. Moving deck chocks has a large impact on the D1 tension.

Measure pre bend by pulling the most forward main halyard down to touch the back corner of the lowest bit of the mast track just above the gooseneck (see image). Pull the halyard tight on a calm wind day and then measure the gap between the back of the mast track and the nearest piece of rope. Pre bend is measured at the height of the lowest spreaders. Measure on base with base chocks in and with the runners loose and the boom down. The ideal pre bend is between 40mm and 50mm.

Tuning Matrix

This tuning matrix is developed for the unique 3Di North Sails technology. 3Di is a fundamentally unique construction process leading to lighter and stronger sails.

TWS (kts)

V1 “Shrouds”

(PT-3)

D1 “Lowers”

(PT-2)

D2 “Uppers”

(PT-2)

Forestay

Deck Chocks

4-7

Base -2

Base -3

Base -2

Base -8

Base +1

8-9

Base-1

Base-2

Base -1

Base -4

Base

10-11

Base

Base-1

Base

Base -2

Base

11-12 (Base)

Base (20)

Base (35)

Base (25-27)

Base

Base

12-14

Base

Base +1

Base

Base +2

Base

14-16

Base +1

Base +1

Base

Base +4

Base

16-18

18+

Base +2

Base +3

Base +1

Base +2 (37)

Base

Base

Base +6

Base +8

Base

Base -1

Each turn listed on the tuning matrix above is a 360 degree turn.The numbers in brackets on the tuning matrix are rig tensions.

Battens

A couple of stiffnesses of carbon full length battens in the head of the mainsail (and jib) help to perfect the sail set up across the wind range. North Sails have standard recommended batten upgrade options, please get in contact with a North Sails expert to discuss this further.

Jib Trim

Crossovers

Helix technology in the jibs defies conventional sail design limitations enabling one sail to perform optimally across a wider range of conditions than ever before. Engineered for active camber control, Helix upwind sails enable sailors to radically adjust and control sail shape and power as well as minimizing luff sag by adjusting the jib halyard fine tune.

J1 (J1-3): 5 -11 knots *new design

J2 (J2-1) 10 –17 knots *new design

J3 (J3-3) 15-21 knots *new design

J4 Heavy Weather OSR (J4-3): 20+ knots *new design

Storm Jib: for use to satisfy a class rules requirement instead of taking the J4 sailing.

JIB CARS. It is best in light and medium winds to be max inboard on the car. If out of range, or at the very top of the range, on a jib going one step outboard on the jib car works well. There is jib car height adjustment line next to the main hatch. Car height is the main car tuning tool for setting the depth and twist in the jib.

SPREADER MARKS: It is really useful to have spreader marks on the underside of each spreader. Place these in the center of the spreader and 150mm inboard and outboard of the central mark.

Mainsail Trim

MNi-5: All purpose mainsail *new design

TRAVELER. Maximum height and power are generated by having the traveler all the way up in light winds. In strong winds it is best to not go far below the centerline with the traveler car, use the fine tune to twist open the main. Once overpowered it is fastest to only have the traveler just above the centerline. Easing the traveler is one of the first moves to depower.

RUNNERS. Off in sub 6 kts, then progressively tighter until max combined headstay / tack load of 1.8 tonnes. 1.8 tonnes is the max load according to the builders.

OUTHAUL: Just loose so the sail is not touching the boom below base, and then tighten it when the wind builds.

CUNNINGHAM: Off downwind and in light winds. Progressively pull it tighter as the wind builds, especially when sailing at/over +4 on the headstay. This helps to bend the mast and flatten the mainsail whilst holding the draft forward.

Downwind

Spinnaker Crossovers

A1.5:(A1.5-2) 5-9 knots *new design

A2 Minus (A2 Minus-1): 8-12 knots *new design

A2 (A2-1): 11-18 knots

A4 (A4-3): 18+ knots

A3 (A3-3) Reaching

Techniques

In light airs the kite flies best and the gybes are best with the jib lowered.

In over 8 knots of true wind speed sail VMG angles based on heel and apparent wind / true wind angles. It is fastest to leave the jib up.

RUNNERS. Loosen the runners downwind to generate depth and power. Keep the windward runner snug. When the wind increases, tighten the runners just enough to keep the headstay straight / tight.

Further Information

Please get in contact with a North Sails expert to further discuss techniques and settings.

Ben Saxton - North Sails Class Lead

ben.saxton@northsails.com

+44 7962 238 742

Crossover Chart

READ MORE

READ MORE

NORTH SAILS EXPERT VIEW ON 2024 IRC UPDATES

Optimizing your IRC rating for your specific boat is no simple task. If you find yourself unsure about the ideal sail inventory, we strongly recommend reaching out to our experienced team of experts today.

READ MORE

READ MORE

FIBERS & FABRICS: A SAILOR’S GUIDE

Modern sailcloth begins life as industrial fiber and film. Some of these products are well known to sailors by a specific supplier’s brand name. A better understanding of the characteristics of these fibers can be helpful in choosing the right sails for your boat.

READ MORE

READ MORE

WHEN TO REPLACE YOUR SPINNAKER

Remember when your spinnaker was new—how crisp and clean the material felt and the way it crinkled going into the bag? The whites were white and the colors were bright, and it even smelled like the brand new nylon that it was.

READ MORE

READ MORE

CRUISING SAILS MATERIAL GUIDE

North Sails offers three material options to help you find the right sails for your needs. Every North cruising sails is custom-designed for your boat and sailing style. By matching the right materials to your sailing goals, you'll be even happier with your new North sails. That could mean easier furling and flacking, smoother tacking and jibing, headache-free sail handling and storage or optimum performance and longevity.

Cruising sailcloth comes in three styles: woven Polyester dacron, cruising laminates, and 3D composite material. Each provides a different balance of durability and performance. Dacron fabrics are the toughest and most structurally stable. Cruising laminates offer lighter weight and increased shape holding. 3D composites are a new generation of cruising materials with exceptional shape holding and structural integrity beyond many laminates.

READ MORE

READ MORE

JASI: SUPERYACHT SPEED IN RORC TRANSATLANTIC RACE

JASI: SUPERYACHT SPEED IN RORC TRANSATLANTIC RACE

North Powered Swan 115 Sets Unofficial Superyacht Race Record

📸 Balta Montaner

North Sails and North Technology Group President Ken Read has logged thousands of ocean miles in three round-the-world race programs, over a dozen Transatlantic crossings, and countless high-profile distance races. For the 2023 RORC Transatlantic Race, Ken was a Watch Captain on board Swan 115, Jasi. A true performance cruiser, Jasi completed the 3,200-mile race in an elapsed time of 09 days, 14 hours, 43 mins, and 37 seconds. Notably, this is the fastest time for a superyacht in the nine-year history of the race, besting the previous “unofficial” superyacht record set by the 130ft Baltic My Song in 2018 by 15 hours.

“This was a completely different experience from any other offshore racing I have ever done. When you go down below on Jasi, you walk into a luxurious, quiet, air-conditioned condominium that just so happens to have some pace.” said Read. “On board, the crew takes showers, eats excellent food, and each has a bunk to sleep in. This race was a downwind dream ride, but on a boat of Jasi’s size, you have to manage safety and competitiveness in equal measure.

Up on deck, it was definitely a boat race. The primary mission for Jasi’s owner and his two friends, dubbed the ‘three amigos,’ was to experience a true offshore adventure. And the RORC Transatlantic Race delivered.” Trim, tactics, pace, crew work, sail changes, squalls, watch systems all on a 90-ton superyacht to drive down waves and push like a race boat.

“Jasi, as a sailing machine, was still new to racing. She had done a few inshore regattas but had yet to put on any real ocean miles. We had a bunch of first-time transatlantic sailors on board, and it was fun for me to pass on a bit of knowledge and share my experience, especially with the younger crew members. Hopefully, I helped them avoid some of the mistakes I have made (and learned from).”

📸 Balta Montaner

Learning on the Fly

“Very quickly during this race, the three amigos settled into the watch rotation, and the crew opened up their personal playbooks to start sharing their knowledge of offshore sailing.” According to Ken, wWatching the amigos experience offshore sailing and learning was the trip’s highlight.

The owner made an incredibly quick study of apparent wind driving, and Jasi is a challenging boat to drive. He was fearless, never missing a beat driving through a 27-knot squall. He never thought about relinquishing the helm, nor did it cross our minds to ask him.

Jasi had a team of 21, living together in reasonably close quarters, so like all offshore adventures, everyone had to be on the team. For example, a few days into the race, one of the newbies came up on deck with ten sandwiches. He never would have done that at the start of the race; more likely simply making one sandwich for himself Making ten wouldn’t have occurred to him. “When offshore, it is not just the subtleties of learning how to use a boat; it’s also learning how to be a team player.”

Jasi’s program in the Caribbean will include the famous Supermaxi regatta, St. Barths Bucket. Read believes that the lessons learned in the RORC Transatlantic Race will be of great use at the regatta. “The skills and knowledge learned are 100% transferable to inshore racing.”

View this profile on Instagram

Royal Ocean Racing Club (@rorcracing) • Instagram photos and videos

“In many ways, the Transatlantic was a ten-day practice session for the ‘Bucket. Changing spinnakers, for example, all of the systems and maneuvers will be the same, and during the Transatlantic, we got progressively better and compiled comprehensive speed, angle, and polar data. The big goal for the team and the owner is to finish each day satisfied that we sailed the boat well and let the chips fall on where we stand after time correction.”

Ken knows that there is no question that the transatlantic rookies all went home telling all their friends about their amazing experiences. “We need to bring new blood into our sport, and the RORC Transatlantic is a perfect way to do that. For many yachts who started the race, it was never about winning and losing, but it was about the experience; the stars at night, the marine life, and living offshore.”

📸 Balta Montaner

Jasi’s Inventory: Her Engine Above Deck

Mark Sadler from North Sails Palma, was the project manager for Jasi’s sail inventory and also raced on board for the RORC Transatlantic Race. Mark is a fantastic sailor in his own right and was a watchmate of Ken’s for this trip. For over a decade, Sadler has competed in and supplied sails to many Superyacht, Offshore, and Grand Prix regattas for North Sails. Like all successful teams, its people like Mark and their experience that remain a significant strength for North Sails.

Jasi’s sail inventory is made up of: 3Di Raw 870 mainsail, 3Di Raw 870 Helix J2, 3Di Raw 760 Helix J4, J5 storm jib, 3Di Raw 760 Genoa staysail, Cuben fiber Spinnaker staysail, A1.5 Nylon spinnaker, A4 Polyester spinnaker, A6 Polyester spinnaker, Top Down Furling Helix Code 0, Storm Trysail

Ken recalls, “We may have done about 30-40 sail changes during this race. We used the J2 only at the start and the finish, but the Code Zero saw a ton of use. The J4 was used as a staysail and a Genoa Staysail as a triple-head sail. We had three kites that had plenty of use, and the loads kept working against us. We had to attend to some small nicks after the lazy sheet burned a few holes in the luff sections.“

Worth Noting

One recommendation Read had for future racing with Jasi is to bring a sewing machine on board. Squalls are a huge part of sailing in the ocean, morning, evening, and nighttime, requiring multiple sail changes to ensure they didn’t have too light a sail flying in the more punchy squalls.

This race was a great reminder of the total team effort it takes to pull off any transatlantic race, not just out on the water but also in advance, getting the boat race-ready. Toby Clarke and all the permanent crew did a fantastic job. Read shares “A big thank you to the Royal Ocean Racing Club for providing a safe and well-organised race.”

North Sails powered all of the major winners in the 2023 RORC Transatlantic Race, including Multihull Line Honours winner Maserati, Monohull Line Honours winner I Love Poland, and the Overall Winner, NMD54 Teasing Machine.

READ MORE

READ MORE

INTERNATIONAL MOTH TUNING GUIDE

This guide is designed to add additional support information to sailors rigging their International Moth Helix sails for the first time. There are some fundamental differences with the Helix sail, ‘twin-skin’ split batten technology, compared to previous models. The Helix sail offers a large step forward in performance, however, there are some new learnings required when rigging, which once understood, is neither complicated nor time-consuming.

Initial Set-Up

When your sail arrives the following should be included:

1. 7 x Full Length Split Battens

2. 6 x Decksweeper battens – Glass RB

3. 13 x Rocket Adjusters

4. 6 x mast cups. Numbered 1-6

These battens should be cut to length and there should be no requirement to adjust the length of them. Please contact a North Sails representative if you feel the battens need to be adjusted. Any batten length adjustment should be off the back of the batten and not from the split end.

Batten lengths may vary +/-20mm

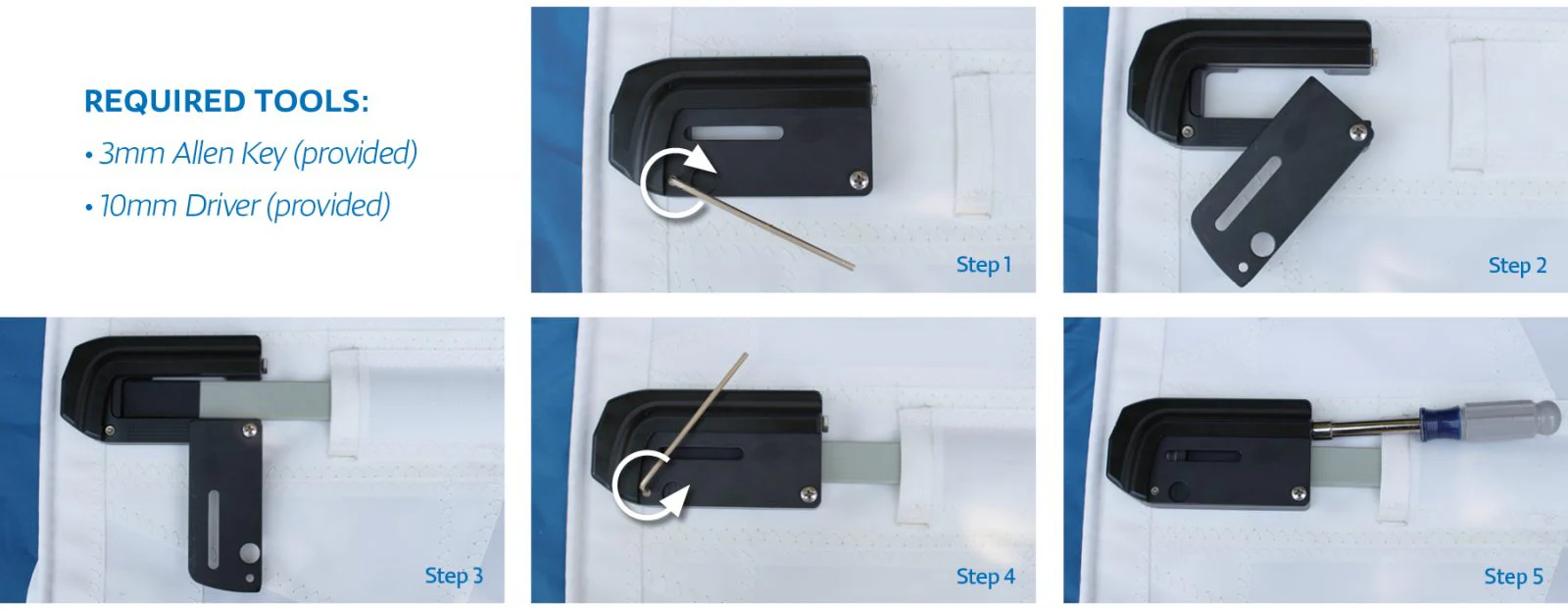

These parts should be fitted, but if not, take the following steps:

Battens

Step 1: Batten Cups

The battens cups need to be threaded onto the webbing strap found inside the luff tube. The webbing strap prevents the cups from moving in a vertical direction whilst sailing, hence the cups grip onto the strap quite tightly.

Once the cups are threaded onto the webbing strap, pass the strap down the luff tube, ensuring to remove any twists from the strap.

The Cups may need adjusting slightly once you are rigged. Follow the impression of the batten along the batten pocket and aim to keep it aligned or fractionally on the high side of the pocket. The webbing strap may be overlength and can be cut to length – around the height of the boom. There is no requirement to locate the lower end of the strap.

Step 2: Batten insertion

Batten #1

The top batten doesn’t have a mast cup. There are however 2 batten pockets on the luff tube, one on each side. The split batten end needs to pass into each of these pockets. The batten pockets are offset so that each of the split tips can be inserted in turn. Put your hand up inside the luff tube from the zip at batten #2. Pass the tip of the #1 batten into the pockets on each side of the sail. This process can be slightly tricky but easily managed and only has to be done once.

Batten #2 - #7

These battens are to be inserted from the rear end and then the split tip is inserted into the receptacles on the rear face of the cups. There are sacrificial pieces of plastic within these receptacles that are designed to break and distort to add friction to the batten and prevent it from falling out. The batten will need to be pushed firmly into the batten cup receptacle. At batten #7 there is a batten holder on each side of the luff tube. Each half of the batten needs to be passed through these.

Add rocket batten tensioners to all battens.

Step 3: Deck Sweeper Battens

There are 6 x deck sweeper battens that can be fitted and rocket tensioners added.

The diagonal deck sweeper battens are the only battens that need removing for de-rigging and sail rolling.

Rigging

Step 1

Insert the mast into the luff tube, as per all previous models, ensuring to pass the mast above the battens and not through any of the split battens.

Note:

Avoid wrapping the mast tip around the webbing strap

At batten 7 there are batten holders on each side of the luff tube, the mast must pass in front of these.

Once the mast tip reaches batten #2, the uppermost batten cup, ensure to thread this batten cup onto the mast (pushing the mast in front of the cup). Continue to push the tip of the mast into the head of the sail.

Step 2

Shuffle the luff of the sail down the mast until you can see the forestay and spreader fittings.

KEEP ALL BATTEN CUPS OFF THE RIG AT THIS STAGE (except for Batten #2 – cup #1)

Step 3

Continue to rig the sail onto the boat. Attach the clew and boom vang. Some pre-bend will be required to attach the batten cups.

Step 4

Once there is some pre-bend, achieved by some vang load, the next step is to put the batten cups onto the rig. Work from the top down, carefully putting each cup onto the rig. Normally twisting them slightly can help to get them on. Once all the cups are on, slide the luff tube downwards and attach the cunningham.

De-Rigging

Aim to do the above procedure in reverse. Remove cups from the rig before releasing the clew. This de-loads the sail and it's far easier to remove spreaders etc.

Tuning & Race Set-Up

Battens

In general batten tension should increase from top to bottom. Aim for one or two small creases in batten #1, one crease in batten #2, half a crease in batten #3, and no creases in battens #4-7. Luff round and sail camber can be tailored with batten tension in the lower battens. Adjusting batten tension to different wind conditions will produce performance variation as the batten tension will increase camber.

Batten cups

When fully rigged with vang and cunningham loads @ 70% ensure the battens run along the batten pockets and the cups are not sitting too high or too low. Aim to have the batten and cup just high within the batten pocket.

There are a few nuances to this new design, but once understood, rigging time is very similar to previous models.

Please feel free to contact Rob Greenhalgh with any questions.

READ MORE

READ MORE

LIGHTNING TUNING GUIDE

Proper boat speed depends mostly on constant and consistent adjustments to your rig and sails. The following measurements are those we have found to be the fastest settings for your new North Sails.

READ MORE

READ MORE

470 TUNING GUIDE

Quick Tuning Guides:

N14-L18 Mainsail

N13-L12 Mainsail

N13-L16 Mainsail

N12-L9B Mainsail

N10-L5 main

N10-L5(H) main

N9-L5 main

L5-N15 Mainsail

See also: Tips for Adjusting the Bolt Rope on Your 470 Mainsail

READ MORE

READ MORE

ZEKE HOROWITZ'S J70 TIPS TO THE PODIUM

ZEKE’S J70 TIPS TO THE PODIUM

Lessons Learned at the Helly Hansen Sailing World Regatta – Marblehead

📸 Chris Howell

As usual, the town of Marblehead pulled out all the stops for competitors to descend upon the quaint New England town for a weekend of racing in multiple one design classes. The J70 class showed up in full force with most of the top American teams including several class World Champions. At stake were two 2 qualification spots for the 2023 Worlds in St. Petersburg (1 open, 1 Corinthian) so the racing was as tight and competitive as ever. As crew for John Heaton on Empeiria, along with teammates Zach Mason and Will Felder, we were fortunate enough to come away with the Championship and a berth in next year’s Worlds. In addition, our North Sails teammates on Smokeshow, skippered by North Sails North American One Design Manager Allan Terhune with Paul Sevigni, North Sails Expert Chris Larson and Dave Hughes finished second, rounding out a weekend to celebrate for North Sails.

Our team was successful at the Helly Hansen Sailing World Regatta Series Marblehead by relying on lessons we’ve learned over the past couple of years. Admittedly part of our success is due to having sailed together for over 2 years and there is really no substitute for being comfortable with and confident in one another – trust that comes with time. However, aside from our team experience, there were past lessons we drew from during this event that helped us stay fast in the wide range of conditions presented. The J70, due to its rig and hull dimensions, is a boat that has a very fine line between being underpowered and overpowered. The conditions in Marblehead exaggerated this characteristic as the wind range was constantly hovering on either side of this fine line. So it was imperative to adjust your sail and body trim to accommodate for either the lack of power or abundance of power since it was rare to have the rig tuned perfectly. Following are some of our tips that should help keep you fast through the transitions in your next race.

Outhaul

The outhaul is one of the controls that’s easiest to ‘set and forget!’ But it’s actually an incredibly important adjustment for your power package. Due to the high aspect ratio (tall and skinny) of the J70 mainsail, the outhaul affects a larger area than it does on a sail with a lower aspect ratio. So a quick ease of the outhaul will put a boost of power into your sail plan to give you something to hike against. Our team has learned to be very diligent with this adjustment when we are transitioning from hiking to bodies in. Zach is our jib trimmer and we try to leave him in the boat the longest so he has a view of the jib as long as possible. If he is in the boat, we leave the outhaul quite loose to power up the main and try to get him hiking. We’re desperate to get him hiking as more righting moment = more speed! At this setting there is probably 6-8 inches between the boom and the foot of the main. As soon as he’s able to get on the rail and start hiking, we pull the outhaul back on to flatten the main and reduce drag. Any time Zach moves in or out of the boat, we make the appropriate outhaul adjustment.

Jib Foot/ Inhaul

How much to inhaul the jib can feel like quite the moving target… and it is. Its important to set the weather sheet in the cleat in a place where the jib trimmer can play it by “banjoing” it on when we need more power and then easing it back when we want to flatten the bottom of the jib and open the leech. When set correctly, this can be done without adjusting the weather sheet in the cleat. Think about your jib lead and inhaul setting similar to how we set the outhaul as described above. In light air or chop, you want more power in the bottom of the jib which means you want more depth in the foot compared to when it’s windy or flat water. A good rule of thumb is to try to get the foot of the jib to contact the cabin house as much as possible to prevent air from jumping through the gap under the foot. If it’s windy, you’ll need to pull the lead back a bit to depower the sail in order to inhaul enough to bring the foot to the cabin house. If it’s light air, you’ll need to push the lead forward a bit in order to provide enough depth in the foot (power) when the foot is along the cabin house. A good range on the jib lead is between 6 – 7.5 holes showing between the front of the car and the forward most factory bolt in the jib track.

Cunningham

The cunningham tends to be neglected just like the outhaul. Most of the time it’s not the most critical adjustment to make but there is a time when it becomes your very best friend. We saw this condition on the second day of racing in Marblehead when the breeze ranged from about 8 knots in the lulls to upwards of 16-18 knots in the puffs. We all know it’s best to set your rig tension for the lulls and do your best to survive the puffs and that’s where the cunningham comes in. For most, if you’re caught with your rig too loose, your first move is to whale on the backstay to depower and keep the headstay tight. But the problem is that without adequate rig tension, the tight backstay will quickly invert or wash out the main sail leaving you with huge overbend wrinkles and that ‘inside out’ look. But your headstay is still unstable making the boat hard to sail. This is when you want to really whale on the cunningham. To be clear, I don’t mean to just take those luff wrinkles out, I mean WHALE on it! Loads of cunningham tension pulls the draft of the main forward, putting some shape back into the sail (un-inverting it). This then allows you to pull even more backstay on to control the headstay. Your leeward shrouds will be doing basketball sized loops – blowing in the wind, but your headstay will be controlled and you’ll still have shape in your mainsail – albeit a flat shape. Will sits all the way forward going upwind and he keeps the cunningham in his hand. If we hit a light spot, he eases the cunningham as I ease the backstay to power up the rig and then as the next puff hits, he trims it on as I trim on the backstay. Keep your eye on the inversion wrinkle that comes out of the clew and goes up to the inboard end of the bottom batten. When overpowered, you want to see this wrinkle only and use the cunningham to eliminate the wrinkles below/forward of it. More cunningham = ability to pull more backstay = more controlled headstay = FAST!

Weight Placement

The J70 likes to have the crew weight forward going upwind. In fact, in light air it’s difficult to get forward enough. Some teams have experimented with sending their forward-most crew just in front of the shrouds and it seems to be pretty quick when the breeze is very soft. It’s also important to know that fore/aft weight placement can help the boat with moding. All other things equal, pushing weight forward tells the boat to point while moving weight aft helps with a bow down mode. In light air, it’s also important to think about body drag through the air. Try to hide the bodies from the wind as much as possible by tucking up to the cabin house or to your teammate in front of you. Also think about how you can position your body to be as aerodynamic and small as possible. Instead of facing forward with your shoulders square to the breeze, scoot forward and rotate your shoulders so they’re more in line with the wind direction. Sounds insignificant but reducing drag is the name of the game,

It seems like no matter how much we learn in the J70, we’ve never learned enough. It’s important to always be thinking critically and creatively about how to get faster. Keep the learning curve steep and watch your results improve! For more in depth information or for any specific questions, don’t hesitate to reach out to your J70 class North experts.

Contact your North Sails J70 North American Experts here:

ZEKE HOROWITZ ALLAN TERHUNE ALEX CURTISS

READ MORE

READ MORE

SOLO TUNING GUIDE

The Solo is a boat with a relatively simple rig. Once you are on the water there is little adjustment possible. It is essential therefore that you get the right rig settings before launching. When setting up a new boat you need to establish the following:

Mast Foot Position

In the past we suggested two mast foot positions, but in recent years when sailing in a mixed upwind/downwind race track I have found I liked the one setting for all conditions so this is what we would recommend. Measuring from the front edge of the mast foot to the outside edge of the transom should be as close to 3065mm as possible. Please see Fig 1, 1a, 1b showing how to take this measurement.

PLEASE NOTE with this setting the boom will be lower, if you have limited mobility, sail at a venue where you are constantly tacking or on a club course with more offwind than upwind please feel free to move the heel aft to a setting nearer 3052 mm to keep the boom higher, make it easier to tack and bias performance more to downwind. Secondary to this is boats prior to approximately 2008 may struggle to move the heel forward to this measurement due to the bulkhead position.

Fig 1

Fig 1a

Fig 1b

Mast Rake

This is controlled by forestay tension. Set the forestay so its tight when the back of the mast hits the back of the mast gate, then release the forestay tension by 2 holes on the adjuster, this is the base rake. For those with a mast cutout [please check your mast manufacturer for warranty on this] you can set the average mast rake with a tape measure, should be set at 5940mm measured using a tape measure on the halyard hoisted to your black band and then to the top aft edge of your transom bar. To ensure the hoist of the halyard is at the correct height the tape should read 5030mm when held down the mast to the top of the gooseneck band, this is then at the correct hoist height and can easily be replicated, now you can proceed to measure the rake. See Fig 2 & 2a showing how to do this.

Fig 2

Fig 2a

Shroud Tension

When the shrouds are just in tension the mast should be 5mm from the front of the gate. If you sail on flat water or are over 90kgs you can sail with tighter shrouds to limit sideways bend, in this case the shrouds can be in tension when the mast is 10mm from the front of the gate.

Centreboard Position

Turn the boat on it’s side and drop the board and mark the handle when the leading edge is vertical (LV), relative to the bottom of the case. Then lift the board until the trailing edge is vertical (TV) and mark the handle. Then mark the handle with 20mm spacings to guide when you lift the board further as the breeze builds.

Mast Chock

Use 1 x 10mm chock to be used as per the tuning matrix below.

Control

0-5 knots

6-10 knots

11-16 knots

17+ knots

Centreboard

Leading edge vertical

Trailing edge vertical

40mm up from TV mark

40-100mm up from TV mark

Chock

Chock behind mast

Chock in front

Chock in front

Chock in front

Kicker

Slack

In tension to stop boom

Tension to control leech

Max. kicker

Outhaul

50mm depth in foot

100mm depth in foot

50-100mm depth in foot until overpowered then tension progressively

Max. outhaul with crease along foot

Inhaul

15mm from back of mast

10mm from back of mast

5mm from back of mast

0-5mm from back of mast

Traveller

Positioned so that boom end is over inboard edge of sidedeck

Positioned so boom end is between inboard & outboard edge of sidedeck

Positioned so boom end is over gunwhale, until overpowered then vang sheet and keep traveller on centreline

On centreline

Cunningham

Slack

Slack snug to remove larger wrinkles on luff

Tension progressively to depower

Tension to depower

Because Solos are relatively easy to sail a boatspeed advantage is hard to find. The settings that have been used for this tuning guide are based around a Solo sailor weighing 8085kg using a Selden D+ mast and North Sail. However these settings still apply providing you use the correct mast and sail combination for your weight.

The settings are dependent on sea state, weight, mast, sail and fitness. So in a force 3 a 90kg helm would be on full power settings whereas a 75kg helm with the same rig would be on overpowered settings. The overlap between settings can be achieved with a combination of rig, sail and centreboard adjustment. There are different ways to achieve the same result. If for example you are caught out with light/medium settings in strong breeze raise the centreboard further, use more kicker tension (to bend the mast) cunningham and outhaul tension.

Use a combination of mainsheet tension, kicker tension and traveller position to find the best speed upwind. As a general rule start in light winds with the traveller positioned so that the boom end is over the inboard edge of the sidetank and mainsheet tensioned so that all the leech tell tails are flying. As the wind increases use more mainsheet tension and ease the traveller to stop the boom getting too close to the centreline. Kicker tension in light winds should be set just slack so that it controls leech twist out of tacks. As the breeze increases and you have to ease the mainsheet to keep the boat flat use kicker to control the leech profile, and adjust the traveller (usually move inboard) to keep the boom roughly over the outside edge of the quarter. Once fully overpowered use kicker upwind to increase low down mast bend and flatten the mainsail and pull the traveller to the centreline and leave it.

In a Solo body position is extremely important. In very light airs your body weight should be centred on the thwart, but do not move forward of this point however light it is. Once you are sat on the side deck move back so that your front leg is pressed against the thwart. As you become fully hiked move back to 150mm from thwart, and then up to 300mm as the wind increases.

Offwind

Use only enough centreboard so that the rudder is neutral when the boat is flat with the following sail settings:

Light Airs

Leave the outhaul on its upwind setting. The inhaul (if adjustable) should be released so its slack. The kicker should be slack or just in tension to stop the leech opening too much in the gusts.

Medium Airs

Ease outhaul so that lens foot is fully eased, ease the inhaul until slack. Set the kicker so that the top batten flies approximately 90 degrees to the boat, this allows the leech to open and maximise speed. If planing is a possibility keep the boat as flat as possible and take the mainsheet 2:1 from the boom.

Heavy Airs

Only ease the outhaul on tighter reaches if you can use more power. Ease Inhaul until slack. Once on the broader reaches and run ease outhaul to allow a little depth in the foot. Set the kicker as for medium airs or ease to depower on the reaches. This is also very quick on the run to allow running by the lee. By spending time on the water preferably with a tuning partner you will be able to establish the right settings for all conditions. This will allow you to concentrate more of your energies on finding the quickest way round the course.

READ MORE

READ MORE

THE SCOW SAILOR'S GUIDE

THE SCOW SAILOR’S GUIDE

North Sails Tuning Guides, Webinars and More

📸 Hannah Lee Noll

North Sails has been manufacturing and designing championship winning scow sails for over forty years and look forward to doing so for forty more. The North Sails One Design team has a long tradition of serving one design fleets all over the country and we look forward to working with you! Our network of local one design experts and dealers are available to help you get the most out of your sails so you can reach your goals whether it is an informal evening race, or the Class Championship. North Sails is continually developing and improving our products and services to enable you to sail faster is not just our goal; it is our obsession.

“The North Sails team will have a presence at every major scow regatta on the calendar, and we’re dedicated to providing the latest tips, tricks and tuning info to get the most out of your North Sails scow designs. We have put a huge effort into modernizing our product line using the best software, best materials and hundreds of hours on the water to refine the designs,” says North Sails Expert, Jeff Bonanni.

Get to Know Your Class Experts

Allan Terhune has won eleven North American Championships (in the Lightning, Flying Scot and Thistle Classes) and was crowned the 2013 J/22 World Champion, a two time E Scow Eastern Champion crew and is the current ILYA MC Scow Champion. Allan is also a class expert in the E Scow, MC Scow, Etchells, J/70, J/80, J/88, J/105, J/111 with many podium finishes in each class. Allan is a resident of Annapolis, MD. In 2007, Terhune was awarded US Sailing’s One Design Leadership Award and named Rolex Yachtsman of the Year Finalist in 2008 and 2013. Allan has been with North Sails since 2007.

Jeffrey Bonanni has won 5 National and North American Championships, including the 2015 E Scow National Championship. He is one of a small handful of helmsman to have won all 6 National Championship trophy races. Jeff actively races in the E Scow, Melges 20, Melges 24 and Etchells classes, as well as coaching the Northeast’s top junior sailors on Barnegat Bay. Jeff currently serves on the National Class E Scow Association’s Board of Directors and is the Commodore of the Eastern Class E Scow Association. Jeff is a resident of Little Silver, New Jersey and a graduate of Boston College, where he was an ICSA All American Skipper.

Eric Doyle – Eric was raised in Pass Christian along the Mississippi Gulf Coast, where he learned at a ripe young that he was hooked on sailing. Eric began his career at North Sails in 1992. Shortly after starting at North Sails One Design, he was hired by Dennis Conner to sail with Stars & Stripes America’s Cup campaign in 2000. Continuing on he raced with BMW Oracle for the 2003 and 2007 America’s Cup campaigns. Eric’s passion is with smaller keel boats like the Etchells, Melges 24, and J/70, but his favorite boat is the Star in which he won the World Championship in 1999 as skipper and the coveted Bacardi Cup in 2019! Eric is currently based in our San Diego Loft and when he’s not racing or coaching he’s constantly working on R&D sails for the One Design team.

Tim Carlson – Tim Carlson has been selling North Sails for over 5 years as a North Sails representative in the Upper-Midwest and offers a wide variety of services to the vibrant sailing scene in the Twin Cities. Tim is proud to serve the members of Wayzata, Minnetonka, and White Bear Lake Yacht Clubs which host some of the most competitive weekly races in the country. While Tim is fluent in the ways of inland lake sailing, he is no stranger to offshore sailing on the Great Lakes. Over the years, he has participated in the Chicago Mac, Bayview Mac, Trans-Superior, and many more.

📸 Hannah Lee Noll

Tuning Guides

North Sails Experts carefully create and update each class’ tuning guide each season and upon the launch of new sail designs. Make sure you are optimizing your rig, sails, and boatspeed by downloading your class’ guide below.

A SCOW

E SCOW – Newly Updated in May 2022

C SCOW

MC SCOW

M-16 SCOW

M-20 SCOW

X-BOAT

Client and Expert Testimonials

“After North updated their sail selections recently the Magnum has been the only sail that I use. Upwind it is easy to trim and keep the boat on rails but downwind is where it really shines. I was sold on it once I realized I was able to keep pace in the light stuff with the smaller sailors. ” – Sean Bradley

“E Scow racing rewards the teams that put in 100% effort around the race track. The boat is so dynamic and fast, you’re always within striking distance of the next pack. My favorite races are not the wins, but the races where we passed thirty boats to finish fifth.” – Jeff Bonanni

“The MC Magnum is a powerful sail. The results are here and we are very confident that the MC Magnum will be a huge success this summer. We made some significant changes to the MC Tuning Guide, including shroud tension and board angles, which are crucial for boat speed. Make sure to check it out! The MC Magnum is a MUST HAVE!” – Allan Terhune

Webinars

North Sails Experts and Class Champions conduct regular webinars to touch on teaching moments from past events, discuss changes to the tuning guides, explain new sail designs and their intricacies and take the time to answer your questions. Take a look through our collection of Scow Webinars, and learn something new from a class expert!

NORTH SAILS SCOW WEBINARS

READ MORE

READ MORE

E SCOW TUNING GUIDE 2022

This tuning guide is for E Scow sailors using the rig with the chainplates at the max aft position with longer spreaders. With this rig, backstays are not required, allowing the skipper to fully concentrate on tactics and boat speed.

BEFORE STEPPING THE MAST

Clean and lubricate turnbuckles, make sure that the top and bottom threaded studs are even in the turnbuckle tube.

Position mast so that base is locked in mast step plate on deck and top end is resting in the boom rest support.

Check all pins, wires, and fittings for wear, and attach upper and lower shrouds.

Pull the forestay down along the top of the mast, pull firmly, and mark the wire with a permanent marker at the top of the mast base casting or where the tube is cut off at the bottom. You will use this mark to measure your mast rake once the mast is in the up position.

Check the spreaders to make sure they are pinned in the forward hole for an all-purpose setting. This puts the spreaders in the aft-most position.

Make sure that all halyards are pulled down and are not fouled.

Using the feeder line that comes up through the mast step, tie this onto the bottom end of the jib halyard and pull the jib halyard through the deck.

Take care not to loose the feeder line through the deck or you will have to re-run through the pulleys inside the backbone.

Using a person on the foredeck pulling on the spinnaker halyard and someone walking up the mast, step the mast and attach the forestay.

After stepping the mast, proper shroud tensions should be obtained.

If you have a new North mainsail with the slug sewn into the sail, remove the screw holding the slug slide in the mast and remove the slug slide.

This slide can be shackled on another sail for use of an older mainsail.

ALL PURPOSE SETTINGS

For base setting of the mast rake, start by measuring up from the top of the deck at the forestay along the forestay wire to the mark on the wire that corresponds to the mark you put on the wire at the bottom of the mast tube. Please refer to the mast rake chart and use the measurement which corresponds to the year your boat was built.

At this point, tighten the upper shrouds (shrouds that go to the forestay) so they measure 37 (560 lbs) on a PT-1 Loos tension gauge. Make sure the uppers are in the aft-most hole in the chainplates and also make sure you tighten each turnbuckle the same amount. If you want to really fine-tune the rig, measure down to the deck at the chainplates using the jib halyard and adjust the intermediates to center the mast athwartship.

Set the lower shrouds at 21 (240 lbs) on the PT-1 gauge and the diamonds at 23 (280 lbs). You will have to work back and forth between shrouds to achieve these base numbers.

Note: If you have a new boat or new shrouds it is important to sail a few times in heavy air to stretch out the rigging before setting permanent marks on the shrouds and the mast rake. Double check the mast rake measurement after tightening shrouds and after sailing in a good breeze.

Rake Setting

The proposed rake settings below are based on the year your E Scow was built.

1998 - 2011

2012 - 2015

2016 or newer

26"

26 1/4"

26 3/8"

Easy Tuning Charts

Note that all recommended turns are from the base settings.

M3 Mainsail / J4 Jib

TWS

6 knots

BASE - 8 knots (2-3 on rail)

10 knots

12 knots

15 knots

18+ knots

Uppers

-

37

+1

+1.5

+2

+3

Lowers

-1

21

+1

+1

+2

+2

Diamonds

-1

23

-

-

+2

+3

Boards

2 holes FWD

1 hole FWD

1 hole FWD

AP

1 hole AFT

2 holes AFT

Outhaul

Smooth

Smooth

Smooth

Smooth

Max

Max

Vang

Loose

Slack Out

Firm

Firm

Max

Max

Cunningham

Loose

Loose

Loose

12" Wrinkles

Smooth

Smooth

Main Traveler

Up 2-6"

Center to up 2"

1/4 to 1/2 to Post

1/2 to Post

3/4 Down or Post

Post

Jib Traveler

Max Up

Max Up

Max Up

Down 2"

Down 3"

Down 4"

Clewboard

2nd Hole From Top

2nd Hole from Top

2nd Hole From Top

3rd Hole From Top

Bottom Hole

Bottom Hole

Tack Height

4"

4"

3.5"

3"

2.5"

2"

MAINSAIL TOP BATTEN - 6-12 knots go to 10180c, >12 knots increase to 10230c

2021 Easy Tuning Charts

Easy Tuning Charts (pre 2022)

Jib Tack Height

Jib tack height at base measured from the deck to the bearing point of the jib tack control line. Mark your control line to ensure you can quickly find your base setting. Adjusting the jib tack in in small increments during a race is a quick way to power-up or de-power the jib and has a more meaningful effect on jib shape than a 1 hole adjustment on the clewboard. See below.

Jib Spreader Mark

18.5"-19" measured from center rivet on front of spreader bracket, alongside the front of spreader.

In most conditions, the jib leech should be at or near this mark. Periodically sight through the mainsail window or from behind the mainsail to check your sheeting is accurate.

RACING YOUR ASYMMETRICAL

We wanted to provide you with some helpful tips so that your learning curve moves upward. Please follow some of these initial tips so that you reach maximum performance right out of the gate. Teamwork is a major factor in this sport. So, work with your team and see what techniques may work for you specifically. The tips provided are a baseline to work from. When setting up your Asymmetrical sheets – be sure to rig them so that you are doing “inside jibes”. The clew passes between the luff of the kite and the forestay. A quick way to ensure this is to lead the tack line over the starboard spinnaker sheet when you rig your sheets. Tack over sheet.

IMPORTANT MAST TUNING AND ASYMMETRICAL TECHNIQUES TO LEARN

As with any masthead spinnaker configuration, the rig is more loaded and will require more attention to rig tuning and some changes in sailing technique.

DIAMOND STAYS

The diamond stays on the mast help to support the mast head spinnaker configuration and the tension on the diamonds is important to ensure that the mast stays pre-bent and in column. It is important to follow the tuning guide recommendations and not stray too far from these numbers. Diamonds that are too loose when it is windy will not support the masthead kite properly and cause the mast to invert. Note: Diamond stays will stretch when they are new and you must check them before and after heavy air races, especially when the rig is new. Diamond stays will also measure differently with different tension on the Intermediates and the lowers.

SPREADERS

Spreaders should always be in the maximum aft setting on the mast to ensure maximum spreader sweep. Note: This is the fast setting for all wind conditions, and this is true for the aft chainplate boats as well as the forward chainplate boats. The upper spreaders are set from the factory with approximately a 6-1/4” sweep when measuring from the back of the mast to a straight line from tip to tip where the wire passes through the tip. Sweeping the spreaders forward will make the top of the mainsail fuller, sweeping them aft will flatten the top of the mainsail.

SIDESTAY TENSION

With the forward chainplate rigs it is important to start to put some tension on the uppers once the breeze is over 10 knots. 400 lbs. On the uppers is necessary to insure that the mast stays prebent when sailing downwind. We recommend sailing with the uppers closer to 600 lbs once the breeze is over 15knots. This is the same for the aft chainplate rigs. With the aft chainplate rigs we rarely go below 600 lbs on the upper sidestay tension.

MAINSHEET TECHNIQUES

It is important with the Asymmetrical to sail at slightly hotter or higher angles than with the symmetrical kites to achieve the greatest performance. This, along with the higher speeds you are achieving will bring the apparent wind angle forward and require the mainsail to be trimmed at a tighter angle. Also, more vang can be carried since you are sailing at hotter angles with more load on the mainsail. Because you are sailing at hotter angles and the A sails are so easy to jibe you should not ease the mainsail out too far on the jibes. The maximum the sheet should ever be eased is about 10’ measuring from the aft corner of the boat to the boom. This technique along with keeping some vang on will help maintain a positive bend in the mast and regardless of backstay tension will help ensure that the mast does not do an inverted bend.

RECIPE FOR MAST DAMAGE

Crew weight should never exceed 675lbs. on an E Scow. The target weight for 4 people sailing in heavy wind is 630-650lbs. Sailing heavier will dramatically increase loads on the boat and rigging and amplifies mistakes made with tuning and mainsail handling. Jibing in heavy air with the vang loose and the mainsail eased out too far can be a recipe for mast problems. This is the single most important thing you need to concentrate on when sailing the A sail configuration. When you go into a jibe do not slow the boat down, go from high-speed mode right into the jibe. I equate this to a high-speed windsurfing jibe. If the diamonds are too loose and the uppers are too loose this will also compound the situation and cause the mast to invert and could cause failure. As with any powered-up masthead configuration you have to learn the techniques to ensure that you are safely performing the maneuvers. Once you understand the mechanics of the rig you will realize how much fun the A sails are and how much easier they are to sail. With the proper mechanics of boat handling and rig tuning, the rigs are very durable and will stand up to a lot of wind. It is very important to stay within the recommended rig settings. Do not overload the shroud tension or the crew weight as this places too much compression load on the mast and boat and can cause failures.

Downwind Asymmetrical Techniques

SETTING THE ASYMMETRICAL

Pull the bow sprit all the way out – Important – You cannot pull the bowsprit out until you break the plane of the windward mark. Only pull bow sprit out prior to hoisting without kite launcher and one pull tack line system.

Mid crew opens the bag and prepares for the kite to exit the cockpit. Only if you don’t have a kite launcher.

Make sure to keep the boat flat when in the hoisting process as this helps keep the spinnaker out of the water. Not as important with kite launcher.

Mid Crew pulls the spinnaker halyard all the way up - Tip – Make a permanent mark on the halyard in the “full up” position so you pull to that point every time.

With kite launcher on hoist countdown, jib crew pulls windward jib sheet in through ratchet and cleats to windward to clear kite launcher hole.

After the halyard is ¼ of the way hoisted, Jib Crew now pulls the tack of the asymmetrical all the way out and then immediately uncleats the jib sheet and properly trims jib.

Helmsperson Tip – on the set it is very important to help your crew out by bearing away a bit on the hoist. This allows the kite to go all the way up with ease. It is important to also make sure the mainsail is not let out too far. The halyard and head of the kite can get hung up behind the spreader delaying the hoist. Keep an eye on these things.

Once the halyard is up your mid crew should communicate “made”. The helmsperson should freshen (head up) right away so that the kite blows away from the rig and then fills.

Limit your mistakes on the set – do not sail too high on the set – this makes it harder to pull the halyard up and the kite will fill early making it harder on the crew. With practice, you can push this limit higher.

Limit your mistakes on the set.

Practice your timing on all of these things and know when you can push the envelope for the ultimate set!

THINGS TO THINK ABOUT AND PRACTICE

When sailing downwind with the asymmetrical we sail with our boards all the way down. In varying conditions, you may want to experiment with pulling your boards up some. This could be especially good in moderate winds and wavy conditions. Practice this technique and find out what is fast for your team. When in doubt though – keep the boards all the way down.

The angle of heel will not vary from the symmetrical kite setup.

It is very important to keep your lines clean and drop coiled. You need to drop coil your spinnaker sheets after every jibe so that the sheet runs free through this maneuver.

Compass – it is very important to watch your compass angles downwind while staying in the freshest breeze on the course. These boats will be going very fast. Angles and wind really make the difference. Watch your compass as much if not more than you do going upwind.

Downwind Sailing Angles – this will vary some. Many think that you have to sail hot and fast in all conditions with this setup. This is not the case. Here is a brief guideline to go by.

WINDS 0 - 8 KNOTS

A higher angle is required so that the boat builds apparent wind. With this speed, you can begin to sail low. As soon as the boat slows even slightly or the boat begins to flatten in angle of heel – you need to head right back up and fire up the speed again. This requires constant attention and focus. One key factor in this condition is mainsheet trim. As your apparent wind moves forward you need to keep your mainsheet trimmed a lot more. Make sure your mainsail is not luffing. You will be amazed as to how the boat reacts to a tighter mainsheet and how much the boat likes to have the mainsheet worked downwind. Practice this. In this wind range, you want to practice float jibes where you bear away slowly and ease the kite out and start pulling it around so it floats around the bow.

WINDS 9-12 KNOT

You can experiment with sailing a lower or deeper angle in these conditions. As the breeze hits and the boat heels, begin to drive the boat down and sail deeper. Work your mainsheet. As you sail deeper the main will need to be eased slightly, but not nearly as far as would for a symmetrical sail.

WINDS 13 - 15 KNOT

This is where it is really fun! Rock and Roll time! Crews should all be on the high side in their hiking straps. The mainsail will need to be trimmed in – almost all the way at times – as your apparent wind is way forward. The Jib Crew will need to work the jib and also the vang. It will feel like you are sailing at a higher angle due to the speed build-up. You really need to get the boat up and rolling – do not sail low or keep people in the boat – put them on the rail and go for a fast ride! The key is the mainsheet, keep the main trimmed. Do not ease the main much through your jibe either! Keep the sail in! In this wind condition you want to perform Mexican jibes, the skipper turns right into the jibe, you trim the sheet tight, strap the foot of the kite, let it back slightly onto the rig on the new windward side of the boat and as the main is coming across you blow the sheet off and trim the new sheet on quickly.

ASYMMETRICAL TAKEDOWNS

The easiest takedowns are the Windward takedown or the Mexican take-down. The leeward takedown is your third option.

WINDWARD TAKEDOWN

Head the boat virtually dead downwind.

Middle crew begins to pull the windward spin sheet around and then the Jib crew releases the tack line shortly after that. You can release the bow sprit line shortly after. With the kite launcher, mid crew counts down 3-2-1 as they start to pull on the kite retrieval line, jib crew uncleats halyard on 0 and then tack line, tailing as they drop to keep the kite out of trouble. All sheets have to run smoothly to keep the kite coming in freely.

Middle Crew - Pull the windward sheet aggressively through the ratchet - all the way back so that the clew reaches the ratchet block. The sail will have inverted. Only if you have no kite launcher.

Middle Crew - Call for the halyard once you have the sail in hand. See #2 for kite launcher.

Helmsperson - Before the halyard begins to drop be sure to steer up slightly so that the sail blows onto the deck of the boat. If you are dead downwind or sailing by the lee the kite will blow out away from the boat and go into the water. This is not good. It is very important that the helmsperson helps out the crew by steering up.

The Middle Crew stuffs the sail into the bag and prepares for the rounding. Only if you don’t have a kite launcher.

MEXICAN TAKEDOWN

This takedown is effective when approaching the leeward mark on starboard tack and you need to jibe to go around the mark. As you reach a 3 boat length circle from the leeward mark you prepare to go into action. The key is that you need to be at about 150 degrees to true wind as you complete your jibe and you sail on port tack to the mark ( as you jibe you need to have the ability to head up on port jibe slightly so that the asymmetrical stays on the deck of the boat. If you come out of the jibe dead downwind the spinnaker will fall right into the water – again, the helmsperson needs to do their job to make the takedown easy and effective). So, your relation to the leeward mark is critical – you want to exit the jibe and begin to reach toward the leeward mark.

You enter the three boat length circle on starboard tack.

Helmsperson calls for a Mexican.

Middle Crew - Be sure to drop the windward board before entering the jibe.

Begin the jibe – the Middle Crew needs to trim the sheet hard so that the clew goes to the ratchet on the port side of the boat. This brings the clew and the foot of the sail to within reach for the takedown.

The helmsperson turns the boat and enters the jibe. As the boom goes across he yells for the halyard release. The Jib Crew needs to release the halyard and the mid crew will already be taking in the retrieval line.

The helmsperson needs to head up so that the sail gets “pressed” into the rig on the port side. The key is to head up so that the sail falls onto the deck and into the rig keeping the sail away from the water.

The crew needs to be on the high side – on this port jibe as you approach the leeward mark – very important if it is windy as the boat will accelerate once you begin to reach to the mark.

The tack line and bowsprit line are the last two items to be released. The Middle Crew needs to stuff the sail into the bag and hike hard as the boat rounds the mark. Refer to #2 on windward takedown for jib crew steps.

Middle or jib crew pulls the board up on the port side as soon as possible or before the leeward mark.

LEEWARD TAKEDOWN

The key here is that the helmsman heads down for an easy takedown.

Release the tack line and trim the spinnaker sheet in.

Release the halyard slowly or with friction for the first 8 feet so that the halyard does not blow out and get hooked on the leech of the mainsail.

Middle Crew stuffs the kite into the bag.

Final release is the bowsprit line which can occur shortly after the release of the tack line.

Takedown with kite launcher:

Helm bears away, mid crew starts retrieval in counting down, 3-2-1 halyard is released, then tack. Flatten boat as much as possible to all crew to windward. Speed on the retrieval line is the name of the game.

SET UP

It is important to follow the North Sails Tuning Guide – I-1 Rig. Follow the amount of rig tension suggested for the varying conditions.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

The angle of heel is very important on an E Scow. Upwind in up to 10 knots, go for a maximum heel, but never let the water get up on the leeward deck. In more wind, sail with the bilge board vertical in the water. Don’t let the boat heel too much when sailing in a chop: it might feel good, but it is not fast. Just make sure that the bilge board is vertical, or that the boat is just a little flatter. When sailing in a lot of chop, be sure to have a very full jib, power up the main by keeping the rake forward, Cunningham off all the way and the outhaul pulled just until the vertical wrinkles disappear. An E Scow travels at very high speeds for a sailboat, and is very maneuverable even though the rudders are only 10” X 16”. Still, it is important for the crew to be in tune with the skipper to help steer the boat. When a big puff hits, the bow has a tendency to blow to leeward, so the jib crew must be prepared to ease the sheet to prevent this. The most important thing to do when tacking an E Scow is to lower the new board at the right time. As the boat is turning through the tack, wait until the bow is just past head to wind to lower the board: if you do this too soon, it just creates extra drag and slows the boat down. Don’t worry about raising the windward board until the boat is up to speed on the new tack. We like to ease the main slightly and then trim it in to heel the boat as we come up into the wind, and then everybody rolls the boat together. In light to medium winds, keep the jib trimmed in until the boat is head to wind and let the windbreak it across. When it starts to get windy it isn’t necessary to roll the boat, but ease the jib sooner so the bow can come up into the wind easier.

TACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS

As far as tactical considerations go, at the start just remember that E Scows accelerate quickly, so it’s important to trim in before the boats around you or you might get rolled right away. If you have the room to leeward, simply put the boat on a tight reach with 15 seconds to go, get it up to speed by the time you hit the line, and make sure you can sail over the boat to leeward. E Scows don’t seem to create much of a wind shadow, so don’t be afraid to sail in someone’s bad air if you think it’s the right way to go, since the gains in a windshift can outweigh the loss of boat speed. These boats sail so fast that you are never out of the race. If you find yourself behind, several good wind shifts can move you right through the fleet. The important thing to remember is to keep the pedal down and never give up. All these generalizations are norms and averages that have proven fast over many years. Some experimentation on your part may be necessary to fine-tune your particular rig and sailing style. Good luck!

READ MORE

READ MORE

E SCOW TUNING GUIDE

This tuning guide is for E Scow sailors using the rig with the chainplates at the max aft position with longer spreaders. With this rig, backstays are not required, allowing the skipper to fully concentrate on tactics and boat speed.

BEFORE STEPPING THE MAST

Clean and lubricate turnbuckles, make sure that the top and bottom threaded studs are even in the turnbuckle tube.

Position mast so that base is locked in mast step plate on deck and top end is resting in the boom rest support.

Check all pins, wires, and fittings for wear, and attach upper and lower shrouds.

Pull the forestay down along the top of the mast, pull firmly, and mark the wire with a permanent marker at the top of the mast base casting or where the tube is cut off at the bottom. You will use this mark to measure your mast rake once the mast is in the up position.

Check the spreaders to make sure they are pinned in the forward hole for an all-purpose setting. This puts the spreaders in the aft-most position.

Make sure that all halyards are pulled down and are not fouled.

Using the feeder line that comes up through the mast step, tie this onto the bottom end of the jib halyard and pull the jib halyard through the deck. Take care not to loose the feeder line through the deck or you will have to re-run through the pulleys inside the backbone.

Using a person on the foredeck pulling on the spinnaker halyard and someone walking up the mast, step the mast and attach the forestay.

After stepping the mast, proper shroud tensions should be obtained. If you have a new North mainsail with the slug sewn into the sail, remove the screw holding the slug slide in the mast and remove the slug slide. This slide can be shackled on another sail for use of an older mainsail.

ALL PURPOSE SETTINGS

For base setting of the mast rake, start by measuring up from the top of the deck at the forestay along the forestay wire to the mark on the wire that corresponds to the mark you put on the wire at the bottom of the mast tube. Please refer to the mast rake chart and use the measurement which corresponds to the year your boat was built.

At this point, tighten the upper shrouds (shrouds that go to the forestay) so they measure 37 (560 lbs) on a PT-1 Loos tension gauge. Make sure the uppers are in the aft-most hole in the chainplates and also make sure you tighten each turnbuckle the same amount. If you want to really fine-tune the rig, measure down to the deck at the chainplates using the jib halyard and adjust the intermediates to center the mast athwartship.

Set the lower shrouds at 21 (240 lbs) on the PT-1 gauge and the diamonds at 23 (280 lbs). You will have to work back and forth between shrouds to achieve these base numbers.

Note: If you have a new boat or new shrouds it is important to sail a few times in heavy air to stretch out the rigging before setting permanent marks on the shrouds and the mast rake. Double check the mast rake measurement after tightening shrouds and after sailing in a good breeze.

Rake Setting

The proposed rake settings below are based on the year your E Scow was built.

1998 – 2011

2012 – 2015

2016 or newer

26″

26 1/4″

26 3/8″

Easy Tuning Charts

Note that all recommended turns are from the base settings.

M3 Mainsail / J4 Jib

TWS

6 knots

BASE – 8 knots(2-3 on rail)

10 knots

12 knots

15 knots

18+ knots

Uppers

–

37

+1

+1.5

+2

+3

Lowers

-1

21

+1

+1

+2

+2

Diamonds

-1

23

–

–

+2

+3

Boards

2 holes FWD

1 hole FWD

1 hole FWD

AP

1 hole AFT

2 holes AFT

Outhaul

Smooth

Smooth

Smooth

Smooth

Max

Max

Vang

Loose

Slack Out

Firm

Firm

Max

Max

Cunningham

Loose

Loose

Loose

12″ Wrinkles

Smooth

Smooth

Main Traveler

Up 2-6″

Center to up 2″

1/4 to 1/2 to Post

1/2 to Post

3/4 Down or Post

Post

Jib Traveler

Max Up

Max Up

Max Up

Down 2″

Down 3″

Down 4″

Clewboard

2nd Hole From Top

2nd Hole from Top

2nd Hole From Top

3rd Hole From Top

Bottom Hole

Bottom Hole

Tack Height

4″

4″

3.5″

3″

2.5″

2″

MAINSAIL TOP BATTEN – 6-12 knots go to 10180c, >12 knots increase to 10230c

2021 Easy Tuning Charts

Easy Tuning Charts (pre 2022)

Jib Tack Height

Jib tack height at base measured from the deck to the bearing point of the jib tack control line. Mark your control line to ensure you can quickly find your base setting. Adjusting the jib tack in in small increments during a race is a quick way to power-up or de-power the jib and has a more meaningful effect on jib shape than a 1 hole adjustment on the clewboard. See below.

Jib Spreader Mark

18.5″-19″ measured from center rivet on front of spreader bracket, alongside the front of spreader.

In most conditions, the jib leech should be at or near this mark. Periodically sight through the mainsail window or from behind the mainsail to check your sheeting is accurate.

RACING YOUR ASYMMETRICAL

We wanted to provide you with some helpful tips so that your learning curve moves upward. Please follow some of these initial tips so that you reach maximum performance right out of the gate. Teamwork is a major factor in this sport. So, work with your team and see what techniques may work for you specifically. The tips provided are a baseline to work from.

When setting up your Asymmetrical sheets – be sure to rig them so that you are doing “inside jibes”. The clew passes between the luff of the kite and the forestay. A quick way to ensure this is to lead the tack line over the starboard spinnaker sheet when you rig your sheets. Tack over sheet.

IMPORTANT MAST TUNING AND ASYMMETRICAL TECHNIQUES TO LEARN

As with any masthead spinnaker configuration, the rig is more loaded and will require more attention to rig tuning and some changes in sailing technique.

DIAMOND STAYS

The diamond stays on the mast help to support the mast head spinnaker configuration and the tension on the diamonds is important to ensure that the mast stays pre-bent and in column. It is important to follow the tuning guide recommendations and not stray too far from these numbers. Diamonds that are too loose when it is windy will not support the masthead kite properly and cause the mast to invert.

Note: Diamond stays will stretch when they are new and you must check them before and after heavy air races, especially when the rig is new. Diamond stays will also measure differently with different tension on the Intermediates and the lowers.

SPREADERS

Spreaders should always be in the maximum aft setting on the mast to ensure maximum spreader sweep. Note: This is the fast setting for all wind conditions, and this is true for the aft chainplate boats as well as the forward chainplate boats.

The upper spreaders are set from the factory with approximately a 6-1/4” sweep when measuring from the back of the mast to a straight line from tip to tip where the wire passes through the tip. Sweeping the spreaders forward will make the top of the mainsail fuller, sweeping them aft will flatten the top of the mainsail.

SIDESTAY TENSION

With the forward chainplate rigs it is important to start to put some tension on the uppers once the breeze is over 10 knots. 400 lbs. On the uppers is necessary to insure that the mast stays prebent when sailing downwind. We recommend sailing with the uppers closer to 600 lbs once the breeze is over 15knots. This is the same for the aft chainplate rigs. With the aft chainplate rigs we rarely go below 600 lbs on the upper sidestay tension.

MAINSHEET TECHNIQUES

It is important with the Asymmetrical to sail at slightly hotter or higher angles than with the symmetrical kites to achieve the greatest performance. This, along with the higher speeds you are achieving will bring the apparent wind angle forward and require the mainsail to be trimmed at a tighter angle. Also, more vang can be carried since you are sailing at hotter angles with more load on the mainsail. Because you are sailing at hotter angles and the A sails are so easy to jibe you should not ease the mainsail out too far on the jibes. The maximum the sheet should ever be eased is about 10’ measuring from the aft corner of the boat to the boom. This technique along with keeping some vang on will help maintain a positive bend in the mast and regardless of backstay tension will help ensure that the mast does not do an inverted bend.

RECIPE FOR MAST DAMAGE

Crew weight should never exceed 675lbs. on an E Scow. The target weight for 4 people sailing in heavy wind is 630-650lbs. Sailing heavier will dramatically increase loads on the boat and rigging and amplifies mistakes made with tuning and mainsail handling.

Jibing in heavy air with the vang loose and the mainsail eased out too far can be a recipe for mast problems. This is the single most important thing you need to concentrate on when sailing the A sail configuration. When you go into a jibe do not slow the boat down, go from high-speed mode right into the jibe. I equate this to a high-speed windsurfing jibe. If the diamonds are too loose and the uppers are too loose this will also compound the situation and cause the mast to invert and could cause failure.

As with any powered-up masthead configuration you have to learn the techniques to ensure that you are safely performing the maneuvers. Once you understand the mechanics of the rig you will realize how much fun the A sails are and how much easier they are to sail. With the proper mechanics of boat handling and rig tuning, the rigs are very durable and will stand up to a lot of wind. It is very important to stay within the recommended rig settings. Do not overload the shroud tension or the crew weight as this places too much compression load on the mast and boat and can cause failures.

Downwind Asymmetrical Techniques

SETTING THE ASYMMETRICAL

Pull the bow sprit all the way out – Important – You cannot pull the bowsprit out until you break the plane of the windward mark. Only pull bow sprit out prior to hoisting without kite launcher and one pull tack line system.

Mid crew opens the bag and prepares for the kite to exit the cockpit. Only if you don’t have a kite launcher.

Make sure to keep the boat flat when in the hoisting process as this helps keep the spinnaker out of the water. Not as important with kite launcher.

Mid Crew pulls the spinnaker halyard all the way up – Tip – Make a permanent mark on the halyard in the “full up” position so you pull to that point every time.

With kite launcher on hoist countdown, jib crew pulls windward jib sheet in through ratchet and cleats to windward to clear kite launcher hole.

After the halyard is ¼ of the way hoisted, Jib Crew now pulls the tack of the asymmetrical all the way out and then immediately uncleats the jib sheet and properly trims jib.

Helmsperson Tip – on the set it is very important to help your crew out by bearing away a bit on the hoist. This allows the kite to go all the way up with ease. It is important to also make sure the mainsail is not let out too far. The halyard and head of the kite can get hung up behind the spreader delaying the hoist. Keep an eye on these things.

Once the halyard is up your mid crew should communicate “made”. The helmsperson should freshen (head up) right away so that the kite blows away from the rig and then fills.