NORTH SAILS BLOG

All

Events

Guides

News

People

Podcast

Sustainability

Tech & Innovation

Travel & Adventure

guides

LET'S TALK CRUISING SAILS

LET’S TALK CRUISING SAILS

10 Things To Look For

Join North Sails expert Austin Powers, Peter Grimm and Bob Meagher for a discussion on 10 things to look for in cruising sails.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

LET’S TALK MOTH WITH TOM SLINGSBY AND ROB GREENHALGH | SESSION THREE

LET’S TALK MOTH WITH TOM SLINGSBY AND ROB GREENHALGH

Session Three

Moth World Champion Tom Slingsby and North Sails class leader Rob Greenhalgh talk us through the in’s and out’s of race day strategy, and provide tuning tips for the newly released 9DSX Decksweeper mainsail in the third webinar, ‘Let’s Talk Moth’.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

NORTH CERTIFIED SERVICE SPINNAKER SAIL CARE

A LOOK INSIDE THE NORTH SAILS LOFTS: SPINNAKER SAIL CARE

Our Certified Service Experts Explain Review and Repair of Downwind Sails

No matter where you are in the world, you can prepare for your next event or be ready for when sailing season picks up again by knowing what to look for when it comes to a healthy spinnaker. A few months ago we published ‘When to Replace Your Spinnaker;’ a how-to on what to look for and advice on prolonging the life of nylon downwind sails. Many of the tips were visual cues for when you’re out sailing, but our service experts also have a process where they can inspect your spinnaker inside our lofts, and help to determine if it’s in repairable condition or if you should think about replacement.

We called on Certified Service managers Bacci Sgarbossa and Nick Beaudoin, from Italy and Australia respectively. Below is an explanation of their simple, but effective process for assessing the lifespan of your spinnaker. This North Sails Blue Book process holds true for spinnakers of all sizes, from one design to supermaxis.

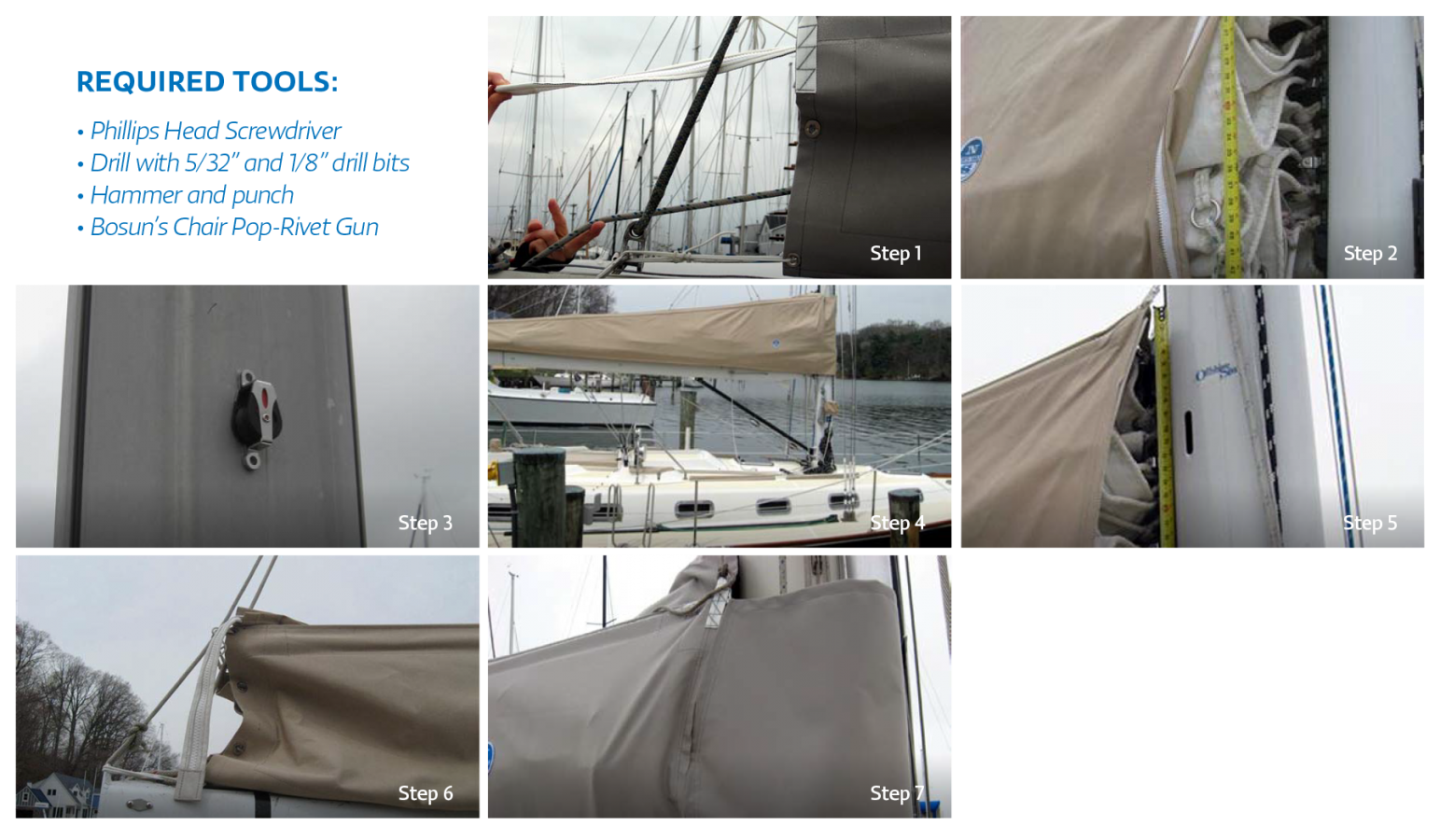

Step 1: Rinse That Salt Off

It’s important to rinse spinnakers after sailing. Salt retains humidity making the kite heavier and more elastic. Plus, dried salt crystals in spinnaker cloth add weight. Let your service expert know if your sail needs to be rinsed when it arrives at the North loft.

Step 2: Hang Dry

Once your spinnaker arrives at the loft, it is draped and hung up to dry overnight. Once dry, it is ready to “fly” (inside!). Depending on the size of the spinnaker, two to four staff “fly” it in the air, which allows the team to get underneath and inspect the sail for any tears and/or holes. As the sail is being flown, damaged areas are marked with fluorescent stickers.

Step 3: Repair

The service technicians use fluorescent stickers to easily identify areas that require sail repair. Pinholes and tears are patched with the appropriate cloth. Once all work is completed, each sail is flaked and bricked for easy transport and storage.

Step 4: Replace (if necessary)

There are times when a sail is beyond repairable. Your Certified Service expert will let you know when the sail is on its last legs and then get you in touch with the proper loft contact.

Find A Loft Find An Expert Request a Quote

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

LET’S TALK VIPERS | LATEST TUNING & TRIMMING TIPS

LET’S TALK VIPERS

Latest Tuning & Trimming Tips

Class Experts Zeke Horowitz, Austin Powers, and Jackson Benvenutti give the latest on tuning and trimming tips, and how to put yourself at the front of the pack.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

LET'S TALK OPTIMIST WITH ANDREW WILLS, DEREK SCOTT AND CHRIS STEELE

LET’S TALK OPTIMIST WITH ANDREW WILLS, DEREK SCOTT, AND CHRIS STEELE

Session One

Optimist class experts Andrew Wills and Derek Scott talk all things Optimist with special guest Chris Steele who won the Worlds in 2007 with Wills as a coach. This session covers planning, daily routine, race routine and how to maintain a good training mindset.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

THISTLE HEAVY AIR TIPS

THISTLE HEAVY AIR TIPS

A Recap From the Midwinters East with Mike Ingham

📸 Cory Hall, St. Pete Sailing Center

Breeze on! The 2020 Thistle Midwinters East was sailed in overpowered conditions for the entire weekend. It was a lot of fun! Going fast was about hiking hard, steering for waves, playing the main to keep the boat flat, and good on board communication.

Here are Mike’s top 5 points on sailing fast in a breeze:

Sail Flat

Flat defined: I define this as a few degrees of heel (not necessarily totally zero degrees flat)

Helm check: You should have no noticeable helm, and to check this you should let go of the tiller and see how fast you head up. You will likely find that at 0 degrees you go straight, and with a few degrees you head up slowly. If you head up at all quickly, you are too heeled!

Hike Hard

Hard hike defined: 100% hike is unsustainable. 80% or something like that is a sustainable hike for long races on multiple race days.

Pain: 80% still hurts! There is no way around it, hiking hard is work.

Your 80%: Everyone’s 80% is different, all you can do is what you can do. Find your 80% and stick with it.

Hike steady: Don’t hike harder in a puff and softer in a lull (assuming the lull is still overpowered as most were at MWE). Sustain that 80%.

DO hike harder in critical situations. Occasionally I would say something like “100% hike until we cross this pack”.

DO hike less when not critical. “50% hike, there is a gap ahead and behind, lets save our energy to the finish”

Vang is a Big Depower Tool

Vang flattens the sail: It bends the mast down low by ‘ramming’ the boom forward into the mast. You will notice more overbend wrinkles when vang is on, less when it is off. More wrinkles means your sail is flatter, less means it is fuller.

Ease in lulls: If you do need power in a lull, ease the vang and sheet in. Still at 80% hike until you are clearly underpowered.

Pull on vang in breeze: If you need to depower more, tighten your vang. There is a limit; our boom bends a lot with vang on full. Our limit is just before we feel we will break the boom.

Main and Steering

Keep the boat flat: To state the obvious, easing the main and steering up keeps the boat flat in a puff, and vise-versa in a lull.

It takes both: It is always a combo of the main and steering, I know of no condition where I do one without the other, its the % of each changes depending on the wave condition

Main and Steering in Waves and Wind

Foot: In waves, pinching up can be super slow because the boat is slowed by waves.

Aggressive steering: I steer all over the place looking for the best path through waves. I find low spots and avoid steep waves, or in smoother waves to steer up the face and down the back.

Steer to waves, trim to heel: To do this, I have to prioritize steering where I need to for the wave while trimming the main to keep the boat flat

Main and steering in flat water:

OK to pinch: In flat water, I can steer wherever I want with no worry that I will slam into a wave

Pinch to depower: In flat water when I am overpowered, I prioritize trying to steer to the wind (up in a puff, down in a lull)

Mainsheet to fine tune: I will still need small main changes to keep the boat flat where I can’t keep up with it steering

It’s Rarely All Waves or All Flat

Most of the time, there is some combo of steering for wind and steering for waves. In the flattest water, 100% of my steering is to the wind because there are no waves. In the roughest water, I probably steer to the waves 80%, and steer to the wind 20%. I would say a typical thistle heavy wind race at MWE was 50% / 50%. The bigger waves I would have to steer through, but flat spots would allow me to steer up in a puff

ALWAYS play the main

Waves: In waves, I am steering a lot through waves, so I need to play the main constantly and aggressively. I go through a large (at times an armlength) range.

Flat: In flat water, even though I want to steer mostly to keep the boat flat, I find I need to constantly adjust the mainsheet to keep the heel just right. These are small (a few clicks here and there) but frequent adjustments

Jib

When we are overpowered, we set the jib to the main backwind bubble. That means when the main is eased a lot, we have to let the jib out too. If our main flogs the jib is to blame (until it blows about 30, then there is nothing left to do but flog both sails!) A gentle bubble of about 1 foot behind the mast is about right. More and you need to ease. Less and you need to trim.

Stay ahead of the curve by calling wind and waves

“Puff in 3, 2, 1 puff on” allows me to start easing at “2” and that prevents an initial heel in the puff. Very effective.

“Big wave”, or even better something descriptive like “Square wave” or “A lot of waves” is super useful.

“Flat spot” is great info on a bumpy day. If there are lots of waves, it seems silly to call them all, I need to just assume there are waves until told otherwise

That should cover it. Sailing flat by being proactive on depowering (vang…), then sailing the right combo of steering and main sheet is the way to go fast in big breeze. Oh yes, almost forgot – hike hard!

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

LET’S TALK SOLO WITH CHARLIE CUMBLEY & TOM GILLARD

LET’S TALK SOLO WITH CHARLIE CUMBLEY & TOM GILLARD

Tuning the Boat for Speed & Upwind Tips

Solo Class Leader Charlie Cumbley and Class Expert Tom Gillard discuss all things Solo with special guest and Solo Class Chairman, Doug Latta. Topics include tips on how to maximize speed on the racecourse, boat setup advice as well as a focus on upwind sailing with Charlie and downwind sailing with Tom.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

LET’S TALK MOTH WITH ROB GREENHALGH | SESSION TWO

LET’S TALK MOTH WITH ROB GREENHALGH

Session Two

North Sails Moth Class Leader Rob Greenhalgh is joined by North Sails designer Ruairidh Scott and Chris Dixon from CST Spars for the second live session for the Moth class.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

LET'S TALK J/70 | MAINSAIL TRIM

LET’S TALK J/70

Mainsail Trim

In this J/70 Webinar class champions Giulio Desiderato, Zeke Horowitz and Allan Terhune talk in detail about mainsail trim and onboard communication.

Topics covered include:

3:02 How do you do your initial J/70 setup

7:35 J/70 Controls. Which and How to Use?

37:24 J/70 Light Wind

47:15 J/70 Medium Wind

53:39 J/70 Strong Wind

1:03:30 J/70 Downwind

Learn more about North Sails fast J/70 designs.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

JOIN NORTH SAILS AND SPECIAL GUEST TOM SLINGSBY TO TALK MOTHS

TUNE INTO A LIVE MOTH WEBINAR WITH TOM SLINGSBY AND ROB GREENHALGH

2019 World Champion Joins North Sails for Let’s Talk Moths Webinar Series

Join Moth World Champion Tom Slingsby and North Sails class leader Rob Greenhalgh live on Wednesday, April 8th for the third session of Let’s Talk Moth. These two world-renowned sailors will take us through the in’s and out’s of race day strategy and provide tuning tips for the newly released 9DSX Decksweeper mainsail.

Sign up and register today for the Zoom link.

Register Now

Session 1: Expert Opinions and Introductions to the North Sails Class Leaders

North Sails Moth Class Leader, and National and European titleholder Rob Greenhalgh gives his expert opinion on a variety of topics and introduces key people within the class. Topics include an introduction to the series, a fleet update, and foiling like a pro.

Session 2: Sail Design, Spars and 3Di for the Moth Class

North Sails Moth Class Leader Rob Greenhalgh is joined by North Sails designer Ruairidh Scott and Chris Dixon from CST Spars for the second live session for the Moth class.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

LET’S TALK MOTH WITH ROB GREENHALGH | SESSION ONE

LET’S TALK MOTH WITH ROB GREENHALGH

Session One

North Sails Moth Class Leader and National and European titleholder Rob Greenhalgh gives his expert opinion on a variety of topics, and introduces key people within the class in the first of many live sessions for the Moth class. Essential topics include an introduction to the series, a fleet update, and foiling like a pro.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

LET'S TALK VX ONE | JIBES & DOWNWIND MODES

LET’S TALK VX ONE

Jibes & Donwind Modes

Tune in with North Sails VX One expert Mike Marshall for an interactive web talk on the different types of jibes and downwind modes.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

LET'S TALK 'OFF THE WIND' SAILING WITH AUSTIN POWERS

LET’S TALK OFF THE WIND SAILING WITH AUSTIN POWERS

North Sails expert Austin Powers and Broad Bay Sailing Association discuss modern advancements in off the wind sailing.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

LET’S TALK LIGHTNING | CHANGING GEARS

LET’S TALK LIGHTING

Changing Gears

Lightning Class Expert Brian Hayes and special guest Greg Fisher share tips on how the top teams change gears and keep the boat going fast in this interactive live session.

READ MORE

READ MORE

![LET’S TALK OPTIMIST WITH HUGO ROCHA [PORTUGUESE]](http://www.northsails.com/cdn/shop/articles/2020-04-09_72683859-8cf2-442d-bdf3-9cd855b1ad75.jpg?v=1685171256&width=1920)

guides

LET’S TALK OPTIMIST WITH HUGO ROCHA [PORTUGUESE]

LET’S TALK OPTIMIST WITH HUGO ROCHA

Session One

North Sails Optimist expert and winner of several World and European titles, Hugo Rocha, gives his opinion as an expert on various topics alongside guest Olympic sailor Jorge Lima.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

CRUISING SAILORS TOOL KIT

We’re All About Your Next Adventure

Our experts have created a variety of articles to help you gain confidence for your next getaway. Topics include battens, weather, safety, durability of cruising sails, and more. Whether you are leaving land behind or simply sharing leisure time with friends and family, our North Sails Cruising Tool Kit will help you prepare for your next trip.

Forecasting For Your Trip

Libby Greenhalgh has navigated around the world twice with the Volvo Ocean Race; she’s a director with the Magenta Project and has an offshore resume that ranks her among the top sailors in the world. Greenhalgh sat down with North Sails to share her steps for planning a trip offshore.

Learn More

Installing and Tensioning Your Battens

Thinking about battens? Preparing for a new season is something that is on everyone’s mind. Whether you’re staging your boat to launch or planning an extended cruise, it’s important to make sure you’ve got your battens installed properly and tensioned correctly.

Learn More

Furling Sails & UV Suncovers

What happens if you furl your sail the wrong way? – with the sun cover on the inside instead of the outside of the furl? Learn more from Expert Hugh Beaton on how to prevent UV exposure and a bad furl.

Learn More

Safety Always Comes First

Hardcore ocean racers and coastal cruisers alike should all make safety at sea a priority. Practices from racing in the World’s toughest conditions of the Southern Ocean can be applicable to sailors of all levels and speeds. North Sails President, Ken Read, shares his tips for all sailors on his best protocols for sailing offshore.

Learn More

Cruising Sailors Demand Durability

Predicting durability is a tough challenge, because sails are subjected to so many different forms of use and conditions. That said, the most common question we hear from cruising sailors is: “How long will my sails last?”

Learn More

Sources Of Power

Cruising sail trim priorities will vary depending on the wind strength. The easiest trimming condition is moderate winds of 8 to 10 knots, because you trim for full power and indicators like telltales are easy to read. Here’s how to set each source of power.

Learn More

Interested in North Sails cruising sails? Contact your local loft today.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

KEN READ ON OFFSHORE SAFETY

Hardcore ocean racers and coastal cruisers alike should all make safety at sea a priority.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

WHY CHECKING THE FORECAST MATTERS

Libby has delivered and cruised all over the world. Her experience has given her an exceptional eye for weather. Greenhalgh sat down with North Sails to share her steps for planning a trip offshore.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

LET'S TALK J/70 | LESSONS LEARNED IN MIAMI

LET’S TALK J/70

Lessons Learned in Miami

Keeping the J/70 conversation going with class champions Tim Healy, Ruairidh Scott, and Allan Terhune. This interactive session includes lessons learned at the 2020 Bacardi Invitational and J/70 Midwinters.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

LET’S TALK FLYING SCOTS | CHANGING GEARS

LET’S TALK FLYING SCOTS

Changing Gears

Join Class Champions Zeke Horowitz and Brian Hayes for an informal web talk covering tips on how the top teams change gears and keep the boat going fast!

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

SAIL CARE & MAINTENANCE TIPS

SAIL CARE & MAINTENANCE TIPS

Ways You Can Protect Your Investment

📸 Cate Brown / Block Island Race Week 2019

There are many ways you can help prolong the life of your sails. Here are some pointers to keep you aligned with our sail care maintenance practices, which can be part of your regular routine while on your own whether you are at home, or on your boat. Preserving the life of your sails is important for performance and you can take these guidelines to help protect your investment.

Avoid prolonged flogging of sails. Flogging and leech flutter can degrade a sail’s performance before its time. Minimize motoring into the wind with flapping sails. After hoisting sails, trim promptly and steer a course so the sails fill rather than flog.

Use your sails in their designed wind ranges. If you don’t know the recommended wind ranges for your sails, contact your North sailmaker.

Adjust your leech line to eliminate leech flutter (tension it just a touch more than necessary to stop the flutter). The tension needed will change as the breeze increases and as the jib sheet is adjusted. Do not over-tension the leech line; if the leech becomes hooked, ease it off. Proper placement of genoa cars will also prevent leech flogging on your genoa.

📸 Michael Egan/ Egan Images

Avoid unnecessary contact between sails and standing rigging. Avoid releasing the genoa sheet late in a tack. Backwinding the leech against the windward spreader tip will distort the leech and can split your sail.

To combat chafe, be sure to cover spreader ends, and check there are no exposed split pins, cotter pins, or other sharp edges around the mast, foredeck, lifelines, and turnbuckles. These can chafe and/or tear your sail.

Make sure your sails have extra reinforcement in areas of high chafe. Spreader patches on overlapping genoas and mainsails, as well as extra chafe protection on headsails where they come in contact with mast mounted radars and stanchions, will extend the useful life of your sail.

📸 Michael Egan/ Egan Images

When leaving the boat, ease the jib halyard, main halyard, and outhaul to prevent permanent luff and foot stretching. Releasing batten tension also reduces distortion at the batten ends

Limit exposure to the sun for extended periods of time. UV rays are one of your sail’s worst enemies. Roller furling genoas should have UV-resistant material covering the leech and foot. If you store your mainsail on the boom, make sure it is always covered when not in use.

Rinse your sails with fresh water and dry thoroughly before storing, to prevent mildew and color bleeding in spinnakers. Rinse fittings in fresh water to help prevent corrosion. Store dry sails in a well-ventilated location. And remember, making sure they are dry is as important as the initial rinse. Wet sails create mold issues.

Avoid folding sails on the same fold lines so that small creases don’t become permanent.

📸 Michael Egan/ Egan Images

Remove mildew stains on polyester, Spectra/Dyneema or Vectran sails promptly. Use a mild household bleach solution with water and a soft cloth, then rinse thoroughly. DO NOT USE BLEACH ON NYLON, ARAMID, OR LAMINATED SAILS.

To remove oil/grease stains, scrub with Simple Green and a soft brush, then rinse. Follow with a mild soap scrub and rinse to remove the Simple Green completely from the sail. Be careful not damage the sail with excessive scrubbing. Depending on the stain, you may not be able to remove it completely.

Removing rust stains is tricky. We recommend that you contact your North Certified Service expert for treatment. We may not be able to completely get rid of it, but we can make sure the area is still in good working order.

Regularly rinse sail bag zippers or lubricate with silicone spray.

Patch minor tears as soon as possible with a pressure sensitive adhesive (PSA). Avoid using duct tape!

Check nylon/polyester downwind sails a few times each season for small tears. Catching small holes early can reduce the chance of them becoming bigger tears later on.

Spray luff tapes on both genoas and mainsails as they slide up the track, using a Mclube-style lubricant. This will help clean the tracks and make hoisting and dousing easier.

📸 Michael Egan/ Egan Images

Check battens for splintering. Splintered battens should be replaced, or at least taped, so the splinters don’t harm the sail.

Check luff slides and other hardware to make sure they are still securely attached to the sail.

Check seam stitching to make sure it is still intact. UV can quickly damage certain threads.

Have your North Sail Certified Service expert inspect your sails at least once a season. Regular inspection will prevent small problems from becoming big ones. You can also ask your local loft to create an onboard sail repair kit for your specific sails.

Keep a sail log. Photographing your sails on a regular basis and logging the hours they are used will help you and your sailmaker evaluate your sail inventory seasonally. Your sail photos can also be digitized and analyzed using North’s SailScan computer program. Contact your North representative for details.

📸 Michael Egan/ Egan Images

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

ROLLER FURLERS & UV SUNCOVERS: WHAT YOU SHOULD KNOW

ROLLER FURLERS & UV SUNCOVERS: WHAT YOU SHOULD KNOW

Understanding Your Furler and How it Works Will Prevent Disaster

📸 Billy Black

What happens if you furl your sail the wrong way? – with the sun cover on the inside instead of the outside of the furl? Unfortunately, we see the effects of this in our service lofts around the world. The result is UV damage to the sailcloth that has been left exposed to the sun, instead of being protected by the UV leech and foot cover.

Most often, this happens when a sail has a UV cover that is the same colour as the sail material. Such as a white cover on a white sail or a grey cover on a grey sail. When the sail is rolled around the headstay in the wrong direction – with the UV protection on the inside of the roll, it is not always obvious leaving the base sail material exposed.

In some cases, this can happen on a new sail that has been installed incorrectly – with the sail cover that is on the inside of the furl due to the direction the furling drum turns when furling – either clockwise or counter clockwise.

This also can happen seasonally when the boat is unrigged or mast is not stepped (assembled and placed vertical). If the furling line is re-rigged, it must be wound the correct direction around the furler, to be compatible with the sail. Fortunately, North Sails always have a sticker displayed as a visual reminder that the sail is furled the correct way based on what side the UV protection is applied.

📸 Michael Egan/ Egan Images

To avoid this mistake which may result in the need for a sail repair, here is a short checklist to ensure that your sail is installed with the UV protection on the outside:

Determine which side of the sail has the built in UV protection – for coloured UV materials this is easy – but not as much as matching colors. The UV cover is either on the Port or Starboard side of the sail. If there is any question regarding which side of the sail is protected please contact your local North Sails professional for assistance. There are many easy ways to tell which side your UV protection is attached.

Next, you want to check that the furling line has been loaded into the drum so that the sail will roll with the UV on the outside. An easy rule to follow is that the furling line needs to enter/exit the drum on the opposite side than the UV protection. i.e if the UV is on the PORT side of the sail, then the furling line needs to exit the STARBOARD side of the furling drum.

Normally, it is a very easy fix to re-rig your furling line, by unwinding it completely, then re-winding it in the opposite direction.

Once you are certain that your furling direction is in sync with your UV protection, you can be confident in leaving your sail hoisted and furled for extended periods of time. Please note, the type of UV material and your latitude make a substantial difference in the length of time and level of protection you can expect from your UV leech and foot covers.

📸 Michael Egan/ Egan Images

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

LET’S TALK VX ONE | TUNING FOR SPEED

LET’S TALK VX ONE

Tuning the VX One for Speed

Join North Sails expert Mike Marshall for the first session of the VX ONE informal web talk about sailing even if we can’t physically go and do it.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

SPEED READING: HOW TO MAINTAIN FOCUS OFFSHORE

SPEED READING: HOW TO MAINTAIN FOCUS OFFSHORE

Day After Day, Mile After Mile, for Extended Periods of Time

📸 Yann Riou

Day after day, mile after mile, distance racing reminds us of that never-ending feeling of being stuck in one place for extended periods of time. Hear more from Casey Smith (CS) how to cope with those long periods of isolation where you can only do so much. Casey is a two-time Volvo Ocean Race veteran and was a key member onboard during all of Comanche’s record runs and race wins. Casey knows a lot about being stuck out at sea, but still finds humor in the little things and gets his job done, which is most important.

Here are Casey’s tips for maintaining focus while isolated at sea for days on end:

What’s the longest race you’ve done?

CS: For sure, it’s the Volvo Ocean Race. Four hours-on, four hours-off, the whole way around the world. Waking up and coming on deck, “Oh, hi. Fancy seeing all you guys here! And look, that other boat we are racing against is still right there, and it has been for the last week!”

Do you have a sequence of things you think about that help you stay focused?

CS: Sleep. Eat. Four hours on watch. Repeat (10, 20, 30+ days…).

Do the days blend together or do you lose track of time?

CS: You lose track of the days of the week. You never lose track of time because the whole boat revolves around time. The four-hour watch rotation or the weather schedules and boat position schedules are all very closely followed, and everyone wants as much time to rest as possible and also know how you are doing on the fleet.

📸Yann Riou

What are some things you think about while you are sailing for extended periods of time?

CS: You just need to concentrate on the competition aspect of the race; that’s why you are out there in the first place. Compete and try to win. It’s really important to put everything into sailing the boat 100%.

How do you maintain your focus if the weather gets rough and you are on the same tack/jibe for hours on end?

CS: Focus comes from wanting to win. Chances are if it’s windy and downwind are probably going fast. You want to make sure you are the fastest boat and keep the pedal down. If you’re sailing upwind, and conditions are windy and rough, that’s a bit tougher because it’s hard to sleep during the off-watch and your energy is a bit lower. Being on the same tack or jibe for long periods is great as it means you get a break from moving sails and equipment so everything has a silver lining!

What advice can you give to someone who is sailing offshore for their first time in relation to staying focused and not feeling overwhelmed?

CS: It’s all about making the boat go fast. Basically nothing else matters. You have a job to do, it might be helming, trimming, grinding, sail changing and everyone contributes to miles gained or lost. Do your job at 100% and keep the boat moving fast. Also, stay calm and level. There will be times when another boat (or boats) is doing better than you but stay calm and keep sailing your boat 100% as that’s all you can control.

📸James Blake

When you are down below, if you are not sleeping, what do you do to still stay alert and ready for when it’s time for your shift to start?

CS: Eat. Make coffee for the team. Tidy up the living space up. Dry water out of the bilge. Check the steering and other systems. Watch movies.

What are your favorite foods to help stay awake and focused if you are the crew on shift?

CS: We are usually limited on what foods we can have on board, so your mind does wander to what food you love and would love to be eating. The reality is you have never seen faces light up as much as when a fresh bag of jerky comes on deck. Coffee and warm drinks are huge as well, but chewing gum is needed after the jerky and coffee. Brushing your teeth is something that slips a little offshore.

Is there anything you have vowed to do when you’ve been on a long leg? (Did you do it?)

CS: Remember to load some more movies, music or books on the iPod. You can only watch the music video of Umbrella by Rihanna so many times.

Staring at the horizon for so many hours on end, have you hallucinated offshore?

CS: No hallucinations on deck but I’ve had some crazy dreams during the off watch. Also waking up and forgetting where you are and then slowly coming too. Then the realization of “crap, I’m on the boat and only one week into a six-week leg from China to Rio.”

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

CRUISING SAIL PERFORMANCE

At North Sails, we are passionate about performance. For cruising sailors, this means a lot more than just speed.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

CRUISING SAIL DURABILITY

Cruising sailors demand durability. Yet, durability is not an easily quantified element of sail performance. Predicting durability is a tough challenge, because sails are subjected to so many different forms of use and conditions.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

DN ICEBOATING: INNOVATING FOR SPEED

DN ICEBOATING: INNOVATING FOR SPEED

What does it take to go even faster than last season?

For Chad Atkins and Oliver Moore, winter means fast apparent wind sailing on their DN iceboats—whenever they can find ice and wind within driving distance of Rhode Island. We recently spoke with them to learn more about a recent speed jump made by North Sails clients. Chad finished third at the 2020 DN North Americans, his first time ever in the top five—and he was just “one bad leeward mark rounding” shy of winning the whole thing. (Tuning partner James “T” Thieler won the regatta.)

Oliver, who owns the Moore Brothers Company and builds iceboat masts, says it’s Chad’s tuning that makes him so fast. Chad, who worked with Mike Marshall to develop the North Sails DN inventory, says it’s those composite masts—and the sails designed to match them—that made his speed jump possible.

But both agree that the most significant speed gains are made long before the regatta starts, which is why iceboaters spend so much time developing and dialing in equipment to suit style, body size, and personal preference. “Most of this stuff is happening before we hit the ice,” Chad says. “Static deflection, bend testing, the development of the mast and the sails and the plank… that’s 75-80% of the speed right there.”

Oliver enjoys that part of the challenge; “It’s the most technical boat I’ve ever sailed, from a setup standpoint.” And he says Chad was the guy who got him into iceboating. “He helped set me up and got me close enough to right that I could be in the conversation. Then you can say, okay, ‘this is the effect I’m trying to achieve.’”

Mast pop

Mast bend characteristics are absolutely critical, and the goal is the same as soft-water sailing: to get powered up as low in the wind range as possible. The ideal look, though, is radically different; the mast is tuned to make it “pop” to leeward. That exerts downward pressure on the iceboat runners, acting (as Oliver puts it) “like a spoiler on a race car,” which makes it possible to push harder without losing control.

“When the breeze builds, the first to get the mast to pop wins,” Oliver says. “So at that point you want a super-soft mast. But as the breeze keeps building, you’re trying to restrain that overbend, because you’re losing power. The way you control that is all in rig geometry: adjusting your shrouds or forestay, and moving your mast.” Once you’re in the ballpark, he says, the entire range is only a couple of turns on the shrouds.

The fuselage (hull) on a DN can vary quite a bit in size and height, but both the length and stiffness of the plank (which runs athwartship and holds the shrouds) are critical. “People are measuring to make sure that when you stand on your plank, it’s bending to the exact millimeter that you think is correct,” Oliver explains. Sails are built to match each mast and plank’s combined bend characteristics, also factoring in other variables like wind strength, ice conditions, and sailor size. “Some people have four or five different sails—I’ve got two.”

Tuning up before Racing

Though the goal is to be in the ballpark speed-wise before showing up to sail, everyone fine-tunes rig tension and mast rake before each race. The mast step can move backward and forward on the fuselage up to six inches, Chad explains. “The farther forward it goes, that’s going to be a narrower triangle , so it’ll bend sooner. The farther back it is, it’ll be a little stiffer.” Though that sounds quite straightforward, Oliver points out that there are other considerations as well. “The farther back you have the rig, the less pressure there’ll be on the front runner. Which can be fast, but you don’t have as much control.”

With so many variables, it’s hard to compare one boat’s tuning to another. “It’s very easy to get completely confused about what’s doing what,” Oliver says, “so I try and simplify as much as I can. If you want more mast bend, ease the shrouds. If you want less, shorten your shrouds.”

Chad says that when he’s going the best, the boat “has some fight to it. I have to work pretty hard to get off the line, get the plank squatting and the mast bending, all the things that need to happen before you can really get going fast.”

If the rig tension is too soft, he says, it affects height. “You might have the same speed, but guys are going to be pointing higher. It’s a pretty noticeable difference.” If the rig’s too stiff, “people are going to be laying down and their leeches start twisting off and they’re just—gone.”

Once the boat is set up the way he wants, Chad gauges mast bend off the forestay, “to know whether to press more (shoulders back on seatback) and keep the boat lit, or ease sheet some and try to get some height upwind—or soak downwind with pressure and angle.”

Between races, sailors often swap out runners or sails to better match the conditions—which can change significantly throughout the day, as rising or falling temperatures affect the ice. “You bring all your stuff out,” Oliver says, “spares and everything, dump your toolbox on the ice. That way you can change things.”

Fast sails

Chad uses the All Purpose Power sail that he helped Mike Marshall design, or the Max Power if the wind is light and the ice soft. Oliver uses the APP as well; “I think the APP works further up the speed range and is more versatile” than older designs, adding that there’s always a tradeoff in DN sailing between versatility and optimization. “Because you can change between races, there is the temptation to have very specialized equipment for each condition—but you still need to figure out which is the right setup. I try to keep it as versatile as possible.”

What’s changed, and what hasn’t

Chad has been iceboating since he was seven. Only a year or two later, “My dad just pushed me off and I went out and didn’t come back.” He laughs. “He’s like, holy crap, I gotta build a second boat.” Since then, Chad has seen the development that used to take place in basements and garages migrate to professional shops like Moore Brothers. Composite masts are more predictable than the spruce or aluminum rigs he grew up with, making DN sailing safer—and a lot more fun. “The technology is really paying off, because you can drive the boat harder and just continue to accelerate another couple of knots.”

Oliver came to iceboating as an adult, and he admits that it’s a pretty crazy sport—especially when you factor in all the driving time that chasing ice requires. But it’s addictive, he says. “The racing at the top-end is insanely amazing—so close, you have one bad mark rounding and you lose the regatta. It’s everything that Laser racing is, but at 40 miles an hour.”

Another thing that keeps both of these guys hooked is the continuous innovation in search of ever faster speeds. “We’ve outgrown some of the smaller ponds that we used to be able to sail on,” Chad says, “because we’re going too fast. But we’re still working to go faster. The aero package part of it’s really starting to come into play, reducing that triangle between the fuselage and the forward top part of the boom… You’re never done, and it’s always fun. That’s what I love about it.” Or, as Oliver puts it: “It’s a radical thing to be going that fast, that low to the ice, crossing ten boats! One good day of sailing every three years—that’s enough to keep you coming back.”

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

J/70 TIPS: HEAVY AIR

J/70 TIPS: HEAVY AIR

Allan Terhune Explains What Worked for Team Vineyard Vines at the 2020 J/70 Midwinters.

When the breeze increases, a different set of skills are required. We caught up with North Sails expert Allan Terhune, who called tactics on the winning team at the J/70 Midwinters in Miami, for some lessons learned from a windy weekend.

Sailing in Breeze – Upwind

The key to speed upwind is keeping the boat flat and balanced. This is achieved two ways: rig tune and trim.

Rig Tune

We were at the top of our tuning guide most of the weekend to keep our headstay tight. One key factor is the backstay gross tune; make it TIGHT. You need to have enough throw to pull backstay on, in order to flatten out the main. Many teams took the slack out of their gross tune but didn’t make it tight. Also I heard many people did not go to the top of the tuning guide. If this was not the weekend to go there, I don’t know what would be!

Trim

Once the rig is tuned, the goal is to keep the helm balanced, and also to be able to burp the main in the puffs to eliminate heel. The key to this is the jib sheet. If you have the sail max in-hauled like you would in lighter conditions, the main would immediately luff in puffs, forcing the bow to go down. To compensate for this, we sailed with less inhaul, and moved the lead forward one hole. This may seem counter-intuitive, but it keeps the leech correct and makes the foot powerful enough to get through the chop. We made sure the leech was close to the middle band on the spreader at all times.

We then played the in-hauler to get through waves and puffs. Our main luffed very few times, and we talked all the time about keeping the boat balanced.

As for mainsail trim, it was easy to over-tighten the outhaul and not have enough power through waves. We found that having max backstay was always faster and having enough vang on made it easy to play the sheet. We tried to NEVER let the main luff or flog. You have to be using both sails to be balanced and fast.

Sailing in Breeze – Downwind

Wow was that fun or what! Seriously though, it was HARD work!

A few things to remember off the wind in big breeze:

Keep a constant angle of heel. Too much heel and you wipe out, too little and you slow down and bear off too much. You have to keep the apparent wind forward.

Jib trim is crucial. Molly did a great job of always keeping the jib full, but also knew when to blow it if I lost the kite.

Jibing: Speed is your friend. The worst thing you can do is bear off and slow down and load the boat up right before a jibe. That is when you wipe out.

Steer around waves and surf whenever possible. Finding a good rhythm with the trimmer and talking about the angles is the best way to identify the path of least resistance.

Stay in the puff. We all work so hard upwind to go .1 or .2 knots faster, but if you miss a puff downwind you will be 2-5 knots slower. The tacticians who keep their eyes out for the next puff make HUGE gains.

This regatta was a great reminder that the J/70 is truly a team boat. Everyone has a role, and if one person is not carrying their weight, the boat does not succeed. For success in heavy air, you need to develop a different set of skills. And practicing with your team when it’s windy is the only way to get better.

Team Vineyard Vines John and Molly Baxter, Ben Lamb, and Allan Terhune are the 2020 J/70 Midwinter Champs after a relentless eight-race battle in a variety of testing conditions. On the final day, they snagged two bullets using the 2019 J/70 Worlds winning inventory: F-1 Mainsail, J-6 High Clew Jib and AP-1 Asymmetrical kite. | Full story

Awesome job team Vineyard Vines. 📸 Chris Howell

John Brim’s Rimette leading the pack 📸 Chris Howell

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN RACING SAILS AND CRUISING SAILS

People use sailboats in many ways, but we broadly define them as cruising or racing. Here is the North Sails Expert advice on what to look for when it comes to performance, design, and materials

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

420 MIDWINTERS: COACH NOTES

420 MIDWINTERS: COACH NOTES

Key Tips To Up Your Game

35 teams from around the country gathered at the Miami Yacht Club for the 2020 International 420 Midwinter Championship. Out of the high caliber of talent, Justin & Mitchel Callahan prevailed with outstanding sailing and a convincing win at this event. North Sails powered boats fared very well, showing speed and versatility in a range of conditions, ultimately placing seven of the top ten boats in the overall results.

Here are some coach notes from North expert Tom Sitzmann:

Know your own boat

As much as we’d love to think that our hulls, spars, foils, sails, and individual tuning measurements are exact, the reality is that each boat, and all gear associated with it, is unique. With a tuning partner, experienced coach, or both, make sure you get out on the water before racing to check your rig settings and sail trim – no two boats are exactly alike! Use tuning guides as a starting point, experiment when able, but proof of concept is only validated on the water.

Spinnaker trim on the reach legs

There are LOTS of gains to be made on the “outer” reach and in the final sprint to the finish. Again, it is critical to know the design philosophy of your spinnaker and trim accordingly. Pole height, often set and forgotten about, can be a big difference-maker for an i420 on the wire reach. Experiment and improve!

Learn more about 420 sails.

Re-tuning for the lighter wind prediction on the final day.

Haul to the open-water sailing east of Key Biscayne

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

THISTLE MIDWINTERS WEST: COACH NOTES

THISTLE MIDWINTERS WEST: COACH NOTES

North Expert Mike Ingham Shares Clinic Tips

📸 Tina Deptula

North Sails expert Mike Ingham hosted a one-day clinic for over 20 Thistles in preparation for the 2020 Midwinters West in San Diego, CA. Boats were overpowered at first, but later in the day, the wind softened.

“It was nice to see both wind ranges,” Mike says. “Reviewing the on-the-water videos, I found some common threads that were well worth talking about with the group.”

If you couldn’t be there, here’s what Mike saw.

Flat, Flat

The Thistle likes to sail flat, especially in Mission Bay where there are no waves.

Depowering

To keep flat when overpowered, you need to depower. Here are a few thoughts on how to do that in flat water:

Outhaul – Tight the outhaul until the foot looks stretched. That shelf is important.

Cunningham – Make sure your main halyard is up all the way and your cunningham is reasonably snug. Wrinkles are great in lighter wind, but as it builds, pull it on to smooth them out.

Pinch – In flat water when overpowered, it is okay to pinch.

Jib Trim

A great starting point is to trim the jib leech in until it lines up with a zip tie taped to the middle spreader 10 ½” away from the mast. A lot of people did not have that zip tie, and their jib trim was inconsistent.

In Heavy Wind: If you have to ease the main out to keep the boat flat, ease the jib as well until there is just a hint of backwind in the main.

In Lighter Wind: When underpowered, if the jib leech tell tale near the middle spreader is stalled, you are trimmed too tight. If it is flowing, you may be able to trim tighter.

Mainsail Trim

When overpowered:

Vang sheet. Pull hard on the vang, and then let the mainsheet out to keep the boat flat.

If you have the North Proctor mainsail, traveler sheet.

When underpowered:

Keep the vang floppy loose so you can control the leech tension with the mainsheet.

As a starting point, try to keep the top main leech telltale flowing 50% of the time (if it stalls behind the main for a few seconds, then flows straight back for a few seconds, that’s 50%)

In flat water, you can have it flow less, say 30%

In waves or chop you will want it to flow more, say 75%

Mike’s next stop – the Thistle Midwinters East in St. Pete.

Learn more about North Sails Thistle sails.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

SPAN SQUARED

SPAN SQUARED

What Does It Mean When Wings Create Lift?

© RedBull G2

When a wing (like a sail or a keel or centerboard) produces lift, an accompanying drag force is generated called induced drag. This is related to pressure that is lost around the wingtip and the formation of vorticity. A wing is considered to be more efficient if it produces lift with less induced drag.

Common understanding is that induced drag is lower for higher aspect ratio wings. This is apparent by reviewing the standard equation used to calculate induced drag which contains the term aspect ratio. The problem with this equation is that it defines the value of the induced drag coefficient using the lift coefficient, which is not necessarily constant depending on how aspect ratio is changed.

The equation is useful in situations where the wing area is the same, such as these two wings. Notice that while they have the same area, they have different spans.

A useful definition is to relate aspect ratio to the span and area rather than to the span and chord. This is particularly handy

for tapered wings.

Lift coefficient and drag coefficient are non-dimensional terms that indicate how hard a wing is working regardless of speed or size. Dynamic pressure, which depends on the velocity squared, and area are divided into the lift and drag forces to define these coefficients. As area changes, the coefficients required to generate the same force will change proportionally.

Since the equation for induced drag coefficient relies on the lift coefficient, it is susceptible to changes in lift coefficient that can occur as the aspect ratio changes. For a fixed amount of lift (force, not coefficient), if the aspect ratio is increased by making the span longer while keeping the chord length the same, which adds area, the lift coefficient will be decreased due to the greater area. If the aspect ratio is increased by keeping the span the same length and decreasing the chord length, then the lift coefficient will be increased due to the smaller area. When aspect ratio and lift coefficient both change, it becomes more complicated to assess what the affect is on induced drag.

There is a simpler way to understand how induced drag is affected. By performing some appropriate substitutions in the induced drag equation and simplifying the terms, we define the induced drag force rather than the induced drag coefficient.

The result is that this equation shows that induced drag is proportional to the lift force (not coefficient) squared divided by the span squared. This means that span, not aspect ratio, is the determining factor for the efficiency of a wing. Area and chord do not appear in the final equation and do not impact induced drag. They do affect the viscous (frictional) drag, though.

Unlike the original induced drag coefficient equation, which implies that induced drag is dependent on aspect ratio (but only when the area is kept constant, meaning that as aspect ratio is changed, chord and span are modified to maintain the same area) this equation demonstrates that the induced drag force is really dependent on the amount of lift squared and the span squared. This reveals that the reduction in induced drag in the previous span comparison example is really due to the increase in span. The power of the squared term is significant because, for example, if span is doubled, the induced drag is decreased by a factor of four. Even a 10% increase in span results in nearly 20% less induced drag.

Understanding that induced drag is inversely proportional to span squared has value to improving sailing performance.

A common misconception is that a centerboard or keel with shorter chord but the same span is more efficient because it has higher aspect ratio. When we recognize that when span is the same, induced drag is therefore the same, we can properly attribute any performance differences experienced to the difference in area. These differences relate to the viscous drag instead, which is the friction of the fluid flowing over the surface and is dependent on the area, and also to changes in angle of attack (leeway and apparent wind) that occur as area is changed.

An example of the affect of span on sails that is common for many one designs is that as speed increases, raking the rig aft has been found to be beneficial to performance. This can be explained through span squared.

After a boat has reached its righting moment limit (crew fully hiked or trapezing, or practical limit of heel for a keelboat) the amount of force that the sails produce cannot be increased any more (without causing excessive and detrimental heeling). In order for the boat to go any faster, the drag needs to be reduced. The longest edge of the sail is the leech, which as the rig is raked aft becomes more vertical and maximizes span. So, with the same lift being produced over a sail with greater span, the induced drag of the rig is reduced and the boat can sail faster. In the most extreme case, comparing an upright luff to an upright leech, the induced drag would be decreased by the ratio of the luff length divided by the leech length, squared.

Another benefit of raking the rig is that the clew becomes closer to the deck, and as the trailing edge approaches being sealed, there is less pressure lost around under the boom and the sail becomes more efficient. Span-wise change in pressure differential is what causes vorticity to be shed from the trailing edge. Increasing the distance between the vorticity shed from either end, or reducing the vorticity shed yield higher effective span, hence lower induced drag.

Since drag also contributes to heeling, a lower heeling force allows the total force on the sail to be increased up to the righting moment limit, further increasing the boat’s speed.

When the rig is raked aft to maximize span by making the leech more vertical, the height of the sail is slightly lowered becoming closer to the water where the wind velocity is lessened by friction with the water surface. While this is not a problem once the boat has reached the righting-moment- limited condition where de-powering (and drag reduction) becomes necessary, it might explain why it is not always advantageous to sail with the rig raked aft in lighter wind conditions when creating more sail force could be the overriding factor.

As the rake of the rig is changed the location of the sail’s force moves with it. This changes the loading required on the rudder in order to make the boat sail straight. While this may limit mast adjustment, the potential benefit creates incentive to discover how to set up the boat to take advantage of the lower induced drag of a more raked rig.

The concept of span squared can also be used to determine the optimum rudder load, either to define the reasonable extent of mast rake or to minimize the drag of the underwater foils for a fixed mast location. The keel (or centerboard) and rudder should both contribute to the boat’s side-force to counteract the sail’s side-force. Determining the appropriate load for each can produce significant performance improvements.

While there are some interactions between the two foils, a simple approach to determine the minimum induced drag is to treat each foil as isolated and sum the drag of each. The result with the least induced drag is that the foils should contribute to side-force proportionally to the ratio of their spans squared.

It is important to consider the span as twice the physical span of the keel or centerboard because it is sealed against the bottom of the hull, which acts as a reflection plane. This is because the pressure differential across the sealed foil is maintained at the hull intersection as if there were a reflected image of the keel protruding upward. A completely immersed rudder that is sealed under the hull can also be considered to have a reflected image that doubles its physical span, but a transom hung rudder that pierces the surface of the water would only be considered to have its physical span without a reflected image. This is because the water surface can deflect due to the pressures imposed on it by the surface piercing foil. As the water surface deflects, the pressure differential at the surface is degraded and the surface piercing rudder loses the benefit of a reflected image.

The difference in effective span between an immersed rudder and a transom-hung rudder indicates that most keelboats (with immersed rudders) should be sailed with more rudder load than most dinghies (with transom-hung rudders).

An additional factor is that as rudder load is increased through deflecting the rudder, the leeway angle of the boat is decreased. Decreased leeway has the additional benefit of a higher apparent wind angle and the opportunity to produce higher sail force. This makes it is very beneficial to deflect the rudder at least to the angle that produces minimum induced drag for the whole boat and gain low induced drag, a higher apparent wind angle and larger sail force, and less leeway, all of which contribute to better pointing. It could even be useful to sail with the rudder deflected somewhat beyond the loading that minimizes induced drag. The small additional increment in induced drag for a modest increase in rudder angle could be offset by further improved pointing ability.

A boat with a gybing centerboard or adjustable flap on the keel already has the capability to reduce leeway and improve the apparent wind angle and may not benefit as much from overloading the rudder as much as a boat with a fixed centerboard or keel.

Since sailing with the appropriate rudder load can have a significant affect, particularly in one-designs where there are limited opportunities for performance improvement, it is valuable to determine what the target rudder angle should be. Assessing the issues for a specific boat requires knowing the dimensions and loads. These can be analyzed to produce specific target settings or designs (if allowed).

Here is an example of how induced drag is minimized through optimizing the load sharing of the keel and rudder.

The total amount of side-force that the keel and rudder produces is kept constant but the amount of side-force that each contributes is varied. By ignoring the affect of each component on the other (a simplification that is more valid as the distance between them is large), the induced drag of the keel and rudder can be calculated separately and added together. In this example the keel span has been chosen to be four and the rudder span to be three. The units do not matter, since we are merely looking at the proportionality of the load. Assuming 100 total units of lift, induced drag is shown for several possible load distributions. Note that minimum induced drag occurs when the load is distributed proportionally to the ratio of the span of the keel and rudder, squared (for example 64/36 = 8/6 squared, and 88/12 is close to 8/3 squared).

The example is shown two ways: with an immersed, sealed rudder that benefits from a reflected image with twice the span, and with a transom-hung, surface piercing rudder that only has an effective span equal to its length. The lower induced drag with the longer effective span rudder is dramatic. But what is important to recognize is that the optimum load sharing distribution is quite different between the rudder styles.

While the longer acting rudder can take 36% of the side-force leaving 64% for the keel, the shorter acting rudder can only take 12% of the side-force leaving 88% for the keel. That causes the lowest possible induced drag value to be 37% higher in order to produce the same 100 units of side-force. Again, the units are artificial, as the constants dynamic pressure and pi have been left out of the equation so we can just look at proportional relationships. A similar amount of drag reduction could be expected for the same style rudder that was replaced with one that had twice the span.

Within the constraints of one-design rules, that type of change is usually not allowed, but there is still the potential to achieve a load sharing that yields the lowest possible induced drag for the configuration. The increases in induced drag as the proportions are varied away from the optimums are shown and give incentive to set the boat up to achieve loads that generate the lowest possible induced drag. Also evident is that being away from the optimum is more severe for the shorter span rudder configuration than for the longer span rudder configuration.

By applying the relationship of span squared, the target loads can be determined for a specific boat. The challenge then is to achieve those loads. This is accomplished through changing the mast position, either by moving the mast step or adjusting rake in order to establish the location of the sails’ force so that the boat will sail straight with the rudder deflected to the desired angle that minimizes the induced drag of the underwater foils. As the mast is shifted aft, the rudder load required to make the boat sail straight increases, and as the mast is shifted forward, the rudder load will decrease. Finding the optimum can have a noticeable affect on performance. The goal is to efficiently use the spans of both foils.

Often, a boat has the mast too upright and hence, is not properly loading the rudder. Raking the mast back can cause the rudder load to increase, which decreases the underwater foils’ induced drag, AND increases the span of the sail by making the longer leech more upright, which causes the sail to have less induced drag also. Appreciating the power of span squared can be useful when making decisions that affect performance.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

SAIL PLAN DIMENSIONS

Determine the Correct Rig Dimensions for Your Sails

When it comes to optimizing your boat's performance, one of the key factors is understanding your sail plan and how its dimensions affect the overall handling and efficiency of your vessel. The basic rig dimensions for a yacht are generally understood. However, there are some differences in how sailors describe these dimensions. At North Sails, we want to make sure everyone is on the same page, which is why we've put together this guide on how we define sail plan dimensions and how to measure them accurately. Whether you're a seasoned sailor or just getting started, knowing how to properly measure your sail plan is crucial for making informed decisions about sail choice and tuning. Let’s dive in!

I – Height of Foretriangle

Elevation of Forestay, measured down to elevation of main shrouds at sheer line.

J – Base of Foretriangle

Horizontal distance measured from front face of mast at deck to position of headstay at sheer line.

P – Mainsail Hoist

Elevation of upper mast band or maximum main halyard position, measured down to lower mast band or top of boom.

E- Mainsail Foot

Horizontal distance measured from aft face of mast at top of boom to boom band or maximum outhaul position.

Is – Height of Inner Foretriangle

Elevation of Forestay, measured down to elevation of main shrouds at sheer line.

Js – Base of Inner Foretriangle

Horizontal distance measured from front face of mast at deck to position of inner headstay at sheer line.

Py – Mizzen Mainsail Hoist

Elevation of upper mast band or maximum main halyard position, measured down to lower mast band or top of boom.

Ey – Mizzen Mainsail Foot

Horizontal distance measured from aft face of mizzen mast at top of boom to boom band or maximum outhaul position.

ISP – Elevation of Spinnaker Halyard

Measured down to elevation of main shrouds at sheer line.

SPL – Spinnaker Pole Length

Distance from the forward end of the mast to the point where the spinnaker pole attaches to the sail or to the pole’s furthest extension.

STL – Spinnaker Tack Length

Horizontal distance measured from front face of mast at deck, forward and horizontally to position of spinnaker tack attachment point.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

EFFECT OF WINTER SUN ON BOAT SAILS

EFFECTS OF WINTER SUN ON BOAT SAILS

UV Is Not Your Friend

We all know that ultraviolet (UV) light breaks down traditional fabrics, which is why sunshine is bad for your sails. (FYI 3Di is composite technology, not a sail laminate. For info on 3Di sail care, read Sail Maintenance.) Even the lower sun angles of winter can wreak havoc on our sails. Here’s what you need to know about UV damage on traditional fabrics. Fortunately, there’s a way to protect your sails and extend their life expectancy: be diligent about covering them up when they are not in use. Once fabric is rotted from UV exposure, the only remedy is replacement. Read on for other factors that make a difference.

Fiber type

Some fibers have better UV resistance than others. For two fibers of the same type, a smaller diameter fiber will degrade more rapidly than a larger diameter fiber. Woven polyester fabrics are made with warp yarns that are almost always smaller than the fill yarn. So when dacron has been rotted by the sun, it will rip more easily across the warp (parallel to the fill).

The simple test of your sail’s fiber integrity is to lightly scrape the surface of the fabric with a dull metal object, like the edge of a spoon or the thick side of a knife blade. If the fibers are still in good shape, the fabric will become shiny and smoother where you rubbed it. If the fibers are rotted, the filaments on the surface will fuzz up or sluff off of the sail. If the UV damage is very advanced, the fiber might rub away completely—the sign of a sail that is going to fail.

Most UV exposure occurs when the boat is sitting with the sails down. Accordingly, some areas of the sail will get more exposure than others. The mainsail leech lying on top will rot long before the parts of the sail hidden beneath it. The same is true for a roller-furled headsail. The fabric on the inside of the roll will last much longer than the leech, which forms the outside of the roll.

Sometimes the degraded area of a sail can be economically replaced. But more often, when the sail fabric is degraded enough to easily rub the fibers away, or to tear a Dacron fabric along the fill yarns, it is time to replace the sail.

Suncovers

You may be surprised to learn that your sail will degrade right through its sun cover. As the cover ages, it becomes less effective at blocking the rays of the sun. Heavier fabric provides a more effective barrier than lighter fabric, and dark colors provide better protection than light colors. If you spend time in the tropics, consider a multiple layer cover. It will be much more bulky, but your mainsail will last longer.

Last but not least, the deck of your boat is an excellent UV barrier. Keep your sails below decks whenever possible.

A suncover can help protect your sail from UV rays, but step one is making sure your sail is furled correctly so the suncover is on the outside. This image shows how the sun has damaged the sail material because the sail was furled incorrectly.

Stitching

Sewing thread will rot in the sun much sooner than a fiber of the same size woven into sailcloth, because it sits on top of the fabric and is more exposed. If resistance to UV rot were the only criteria for selecting the thread weight, bigger would always be better. But selecting thread too heavy for the application will result in a hopelessly puckered up seam and eventually the fabric will tear along the dotted line. A needle that is too small for the fabric weight can bend and deflect around large fibers, adversely affecting the timing tolerances of the machine. With these considerations in mind, the sailmaker typically chooses the lightest thread and smallest needle that the fabric will allow.

Thumb Test

Anyone with a thumb can test for rotten thread. If you can scrape the thread away with your thumbnail, it’s time to restitch your sail. Check each seam in several locations, especially along the leech tabling or on the sail cover of a roller furling genoa. Some areas will rot sooner because of the way the sail is rolled or flaked.

If you can scrape away any of the thread, circle the area with a pencil and then start looking for more rotten thread. Restitching is an easy, time-consuming job, but less time-consuming if you catch the rotted thread before the seams come apart.

Sun degrades stitching. It’s important to get scheduled sail service to address these types of issues to avoid disaster on the water.

Straps and webbing

When you inspect your sails, take a close look at the outside of any web straps. If you see any broken fibers, start planning to get the sail into a loft to have new straps sewn over the old ones. It is not a good idea to attempt to sew through an old

corner strap with an onboard sewing machine, or any other light duty machine. The corners of the sail get harder as the sail is used, and you will be exploding lots of needles.

Excerpted from The Complete Guide to Sail Care and Repair, by Dan Neri

Webbing damage due to long-term sun exposure.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

VX ONE SPEED GUIDE

North American Champion and North Sails Expert Mike Marshall explains how to sail this exciting sportboat well.

Who sails a VX One?

This is the nuts and bolts of VX One sailing. First off, VX sailors are really fun and we all have a blast sailing this boat. Even on a day when we can’t sail, we have a good time. One reason the class is gaining in popularity is that you can sail it with either two or three people, and at a wide variety of weights. Most people sail with three, and the accepted class weight is around 420 pounds. I have been in the top three at major regattas sailing with just one crew, and had great results at weights ranging anywhere from 380-450 pounds.

📸 Tim Olin

What’s involved in crewing?

The boat responds very well to hiking, so it’s important for the entire team to be physically fit. Pulling the spinnaker up and down is the hardest job, so put your strongest teammate in the middle. Sailing with three, jobs are divided up as follows: Upwind: the forward person adjusts the self-tacking jib and the middle crew trims main. Downwind: forward person adjusts weight (both fore and aft and side to side) to keep boat flat and fast, adjusts the jib as needed, and trims the kite during sets and douses. Middle hoists/douses the kite and trims it the rest of the time. Sailing with two, the helm handles the mainsheet and also takes the spinnaker sheet during sets and douses.

Top VX speed tip?

You just can’t get the boat flat enough upwind. Hiking harder will make you flatter, but if you aren’t able to do that ease the main out farther than you think, and then pull the heck out of the vang. Oh yeah, and hike HARD.

What should buyers know when choosing a boat?

There are two builders, McKay and Ovington. Any of the newer boats (above #150) are quite similar. Below that number, the boats are a bit heavier. You are allowed to take weight out of the keel to bring them down to minimum weight, but it’s a little extra work and there is a limit to how much you can take out.

How does a VX get around on land?

For just one boat, the load is light and you can pretty much tow it behind anything. It’s got an aluminum trailer, and the keel goes up and down. So you put the boat on the bunks, put the covers on, put the mast on top, and head off to the next regatta. It’s a similar load to a Lightning. If you are traveling more than an hour, it is a good idea to take your keel out.

How many sails are required?

Three sails, made of polyester cloth. Our goal is to keep costs down. There was a push in the class to go to Aramid, but a brand new polyester sail is going to be better than an older Aramid sail so we think it’s more important to be able to buy new sails more often. That’s also why we only offer three sail options: one main, a jib, and a spinnaker.

VX One Tuning

What are the keys to rig set-up?

The VX has uppers and diagonals, as well as checkstays that attach to the top of the vang, and balancing the tension between them is crucial. Set your rig tension to the tuning guide’s base numbers for the conditions before leaving the dock. Once on the water, fine-tune the uppers so the leeward one just goes slack when you're sailing upwind. That gives you enough prebend, and enough headstay sag or headstay tension for the conditions. Total range is 18 turns from light air to really windy. Once I get my uppers correct, I continue to sail upwind and overtrim the main a few clicks. The overbend wrinkles should go about 50% of the way back. If they're going above the spreaders and more than 50% of the way back, I immediately put a turn or two on the diagonals. If they look okay at the spreaders, but they're going more than 50% of the way back through the window in the main, I put maybe one turn on the checks (the whole range should only be one to two turns, so if you are doing more than that, your base tuning is off). The diagonals will go through about 10 full turns of adjustment up the range. For more detail, read the Tuning Guide. And don’t just count turns; the key is to look at the main while tuning, to dial it in. Then go sailing!

📸 Jeff Westcott

VX One Upwind Sailing

Upwind the front person adjusts the jib sheet and car. It’s self-tacking, but sheet tension and car angle are critical to boat speed. The middle person trims the main, which also controls angle of heel. The driver adjusts vang and cunningham.

Which is better, sailing high or fast?

Sailing fast is much better, but the boat has to be flat. Keep the jib telltales flying 100 percent of time; don’t let the windward one dance until you are overpowered and have to ease the jib out to keep the main from backwinding.

Upwind, where does the crew sit?

Keep crew weight as far forward as possible. If I take three big waves over the bow in a row, everyone moves back a half body width. Otherwise stay as far forward as possible.

📸 Tim Olin

How do you trim the VX mainsail upwind?

Unless we’re overpowered, I trim it in until the top telltale just stalls. Once we get overpowered, mainsail trim doesn’t matter—boat heel does. Ease it out as much as you need to in order to keep the boat flat.

How do you trim the VX jib upwind?

The top of the upper leech should be parallel to centerline with the telltale flying 95% of the time, and the jib car should be sitting at 7-7.5 degrees out from centerline until it’s time to depower. Start depowering by moving the car halfway down the track (10-13 degrees off centerline); I like to keep the sheet on as long as possible. The standard attachment point on the clew is the fourth hole up from the bottom. In breezier conditions, move down a hole or two. Jib halyard tension is key in the VX One and should be played constantly, especially in puffy conditions. When you do have the main eased to keep the boat flat, don't overtrim the jib. If the main starts luffing, it’s backwind from the jib so it is time to ease!

How do you shift gears upwind?

Put the bow down and go faster! Off the starting line, it’s so hard to consistently sail the boat high and slow that you’re better off extending away than trying to pinch someone off. Shifting gears in this boat means figuring out that you’re too high and not fast enough. The faster you go, the more effective the keel and rudder are so the higher you will point.

Who says what when sailing upwind?

On our boat, the forward crew talks about pressure while the middle talks about boat traffic and speed. The skipper has pretty good visibility, and I don’t hike hard enough… so I can look around to decide where to go. When I sail with two, my forward crew talks about pressure and fills in my blind spots.

📸 Jeff Westcott

VX One Downwind Sailing

How fast is the boat downwind?

It feels like you're doing a million miles an hour, but it’s also totally manageable. The boat talks to you; when it does wipe out, just let the kite out, pull the jib in, and get the bow down and the boat flat again. There are two very distinct modes sailing downwind; lower/not hiking, and higher/hiking. The higher mode is better, but harder to maintain because it requires riding the fine line of not sailing too much distance while going fast. The goal is to stay right on the edge of control.

Where does your crew sit when sailing downwind?

The middle crew needs to be able to see the spinnaker, so that means sitting (or hiking) on the weather rail. The forward crew gets as far forward and to leeward if necessary (in light air) to keep the correct angle of heel. It’s easy to move back too soon; wait until you’re planing and hiking or taking waves over the bow. In very light air, the forward crew can sit on the floor in front of the shrouds. Don’t drag the boat’s butt in any condition. If you ever feel like the bow is up in the air, then you're probably too far back.

Under spinnaker, how much heel should be carried?

Just enough to get one half of the hull out of the water, about eight degrees. It’s very similar to upwind.

📸 Chris Turner

What are the keys to trimming the kite?

Biggest key is to ease when a puff hits, even though the kite might curl a little. Trimming heels the boat over, which turns the boat up—the opposite of what you want in a puff. Easing frees the helm and allows the boat to pop onto a plane. In theory, the apparent wind will remain constant downwind, because as you accelerate you turn down. So don’t move the kite sheet too much. In lulls, trim a bit as the driver heads up, but be careful of overdoing it.

How do you shift gears downwind?

There are two modes. Displacement (under 10 knots of breeze) and planing (above 10 knots of breeze). Above 18, it’s easy to find the planing mode. From 10-18 knots, the higher mode is faster but it’s also harder to achieve.

VX One Boathandling

What are your top 3 tips to starting well in a VX?

For the first five seconds after the gun, put the bow down and commit to getting boat speed up. If you do this, you’ll probably be going faster than the boats around you, so you’ll no longer need to sail high to keep your lane. If you don’t commit to the low fast mode, you’ll end up pinching and watching others sail away from you. While in sequence, keep a small part of jib unfurled to make it easier to tack. The jib trimmer needs to be very active. I’d love the jib to come out at 20 seconds, but realistically it’s out at around two minutes to get to the right place on line and control the boatspeed. Never slow down too much. The keel has a very short cord length, so you’ll end up sliding sideways and eating up your hole to leeward.

What are the keys to tacking a VX well?

Keep your crew weight forward. If you drag the stern, you’ll slow down even more. When you come out of the tack, ease both sails to keep the boat flat and powered up until you get back up to speed.

What are the keys to jibing a VX well?