WHAT ARE THE BEST SAILS FOR CLUB RACING?

North Expert Tom Davis lays out your Inventory Options

For some sailors, “club racing” means a casual jib-and-main evening race aboard a well-stocked cruising boat carrying roller furlers and its anchor and chain in the bow. For others, it means a no-holds-barred weekend race aboard a Melges 32 with a full crew aboard.

While there’s no single answer to the question,”What sails are best for club racing?” most club racers will fit into what we call the “cross-over cruiser” category, so that will be our main focus in this article. If you are a cross-over cruiser, you want to race your boat close to home, but you also want a sail inventory suited to sailing with your family and friends during the day and periodically heading out for a weekend or a week’s cruise.

If you want to compete at any level, there are a few things we would recommend prioritizing long before you ever think about choosing the right sails. For example, if you haven’t cleaned your bottom, no sail inventory in the world will overcome a field of grass on the bottom. Second, get the boat set up with the mast straight and reasonably tuned, with your jib leads in position, etc. Maybe look at installing a folding propeller, too. Then it’s time to think about the sails.

What size should your sails be?

Sail size is dictated by your type of boat and rig. Some masts are designed and positioned for large genoa headsails and smaller mains, while others have the opposite. But for every boat, there are usually some choices to make on size.

Most club racing is scored under PHRF or another handicap system requiring you to declare your sail sizes. If that’s the case in your area, do you really know your genoa’s LP (luff perpendicular) and your mainsail girth measurements? If so, have they been reported correctly to your handicappers? Many casual racers find mistakes on their certificates when they take a close look, so talk to your sailmaker; that genoa you thought was a 150-percent LP may only be a 135, and if so your rating is penalizing you unfairly.

Next, think about whether a larger or smaller headsail might make a significant difference in your speed or rating. If your boat is chronically underpowered, a bigger genoa could help. If you are often overpowered, a smaller jib could help you tip over less—and get you a more favorable rating.

You may be able to make some gains with your mainsail, too. If the sail has a smaller girth than what’s listed on your rating certificate—that’s all the measurements from luff to leech, at different heights—you may be entitled to a few seconds per mile of rating benefit. In general, the girths that became standard a number of years ago under the IMS rating rule are still the norm for PHRF. IMS girth mains hit a sweet spot, with a nice-sized roach for extra power but not so much that the sail hangs up on the backstay in light-air jibes. Work with a sailmaker to be sure you’ve got whatever PHRF allows in your area, but don’t push the roach too far; that usually carries a hefty penalty.

What’s the best sail shape?

For most club racers, we recommend first identifying the shapes of your current sails. The best tool for this is a camera; take photos from as low as you can get at the mid-foot, looking up, and share them with your sailmaker.

Shapes become distorted as sail material ages. Usually, the overall draft moves too far aft and the leech profile opens up in the high-load middle and upper sections; both make the whole sail less efficient (slower!). If that’s what your photos show, it’s a good time to start budgeting for a new sail, starting with the worst one—probably the genoa that you use the most. Every season, take the same sail shape photos again to monitor what’s happening, and use what you and your sailmaker see to update your replacement plan.

One note: If your sailmaker isn’t interested in looking at photos of your existing sails, you have the wrong sailmaker. No one can make a really tired sail fast again, but sometimes a little recut or stiffer battens can breath some extra life into your sails.

On most boats, a good all-purpose headsail of maximum size (for your rating) is the single most important sail for club racing. A mainsail with mediocre shape that is paired with a nice headsail is usually a better upwind combination than the other way around.

Downwind, the shapes of your main and headsail matter less than their total area. As soon as you head back upwind, the shape of the genoa is by far the most important.

What’s the right molded sail shape for your boat?

The ideal mold shape for your club racing sails will depend on your boat. Older boats with heavier displacement will need different shapes than newer, lighter boats. This is true for both spinnakers and upwind sails. That’s why it’s best to work with a sailmaker who is already experienced in building sails for your type of boat and has a library of proven sail shapes.

Your sailmaker should also know your local conditions. Are your club races usually held late in the day when the wind is dying off, or is it breezy most of the time?

Older boats also tend to have overlapping headsails, while newer designs do not. That should influence the material chosen for the sail, because it will be important to reinforce the area thats dragged across spreader ends and around the rig when tacking. Genoa sail materials often need to be different than those in non-overlapping jibs, and an experienced sailmaker will be able to address that with a mix of materials.

A flattish shape for a medium-heavy #1 is probably not ideal for a boat with a lot of displacement and an overlapping genoa. Boats like these slow down a lot if you try to point too much, especially on a light air Wednesday night. (If you’re racing in a location with higher average breezes, a flatter sail may be exactly right.)

Another consideration is whether you want two headsails. That way you can use a roller-furling/UV-protected genoa for casual club racing and cruising, then bend on your better “race” sail for more important races. One more tip: if you use a roller-furling sail exclusively, check to see if PHRF in your area will give you a rating credit for it.

What’s the right material for club racing sails?

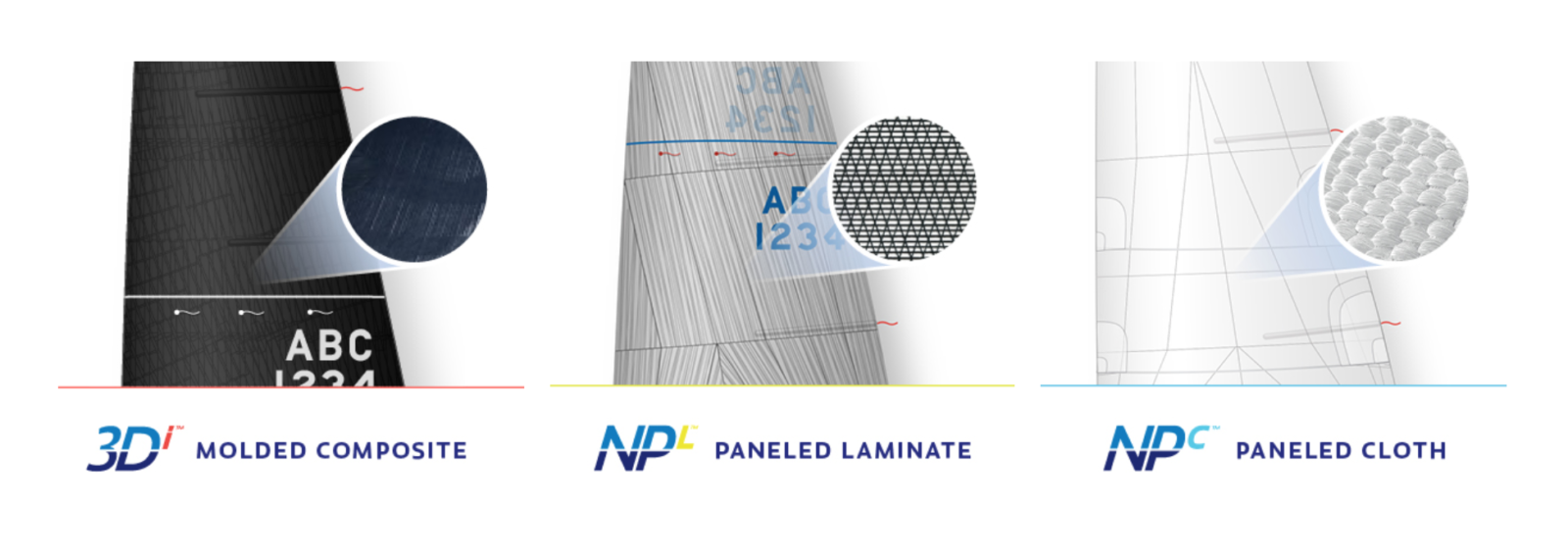

The sail materials you choose will depend on your needs and your budget. Woven Dacron sails for a boat with a small mainsail and roller-furling genoa will be slower than other materials, but if your budget is modest and you want your sails to last a really long time, it’s a perfectly good choice. Just be aware that you’ll struggle to compete against higher performance sail inventories, particularly as your sails age and their shapes deteriorate.

For smaller boats, the loads are light enough that Dacron can stay close in performance. If you own a 34-foot club racer, you might be very happy with sails made of NPC Radian, a patented single-ply woven sailcloth with stretch performance like a warp-oriented polyester laminate. It is a true “Dacron” sailcloth that enables radial panel layouts, but loads are mapped more efficiently than horizontal panels while still providing classic Dacron reliability.

A slightly larger boat of 35 to 45 feet will have higher loads. If you care whether you’re a minute ahead or a minute behind at the end of a long beat, you’ll want higher-performance laminated sails, maybe even 3Di.

Sails made from laminates often have a radial layout. Nearly all sailmakers make these sails, and most others have a laminated film that is more fragile than fiber and has a tendency to shrink. Within the North line, the paneled laminate sail is typically a moderate-priced product with moderate durability and good (but not state-of-the art) performance. Shape durability is much better than classic Dacron, but not as high as North’s 3D materials. The toughness of these sails is quite high.

Many sailmakers make what are often referred to as “string” sails, which are made by gluing spaced-apart yarns between flat outer layers of film in multiple sections—sometimes with additional outer taffeta plies for toughness, or non-woven skins that look similar to North’s 3Di. These horizontal sections are later assembled with added broad-seaming to induce shape. The yarn pattern is intended to follow the predicted loads in the assembled sail.

North Sails’ predecessor to 3Di was 3DL (no longer in production), which was different from current string/membrane sails; 3DL sails were produced in one piece on a full scale adjustable mold, configured to the exact desired foil shape. This eliminated overlapping seams and maintained the continuous integrity of each yarn pass. But 3DL did share one of the less-desirable features of string/membrane sails—thermoplastic “hot melt” glue. We discontinued 3DL in favor of 3Di because 3Di is a much better solution.

3Di has proven durability that is unheard of in other types of sails, both in terms of material and shape stability. Unlike the film and adhesive used in “string sails,” 3Di’s thermoset resin system is extremely rugged and environmentally stable, which means it will not be affected by heat and moisture over time. It also has a high ratio of fiber to resin. The product does cost more to produce, so prices reflect that.

For a club racer, choosing among these options comes down to a sensible match between sail performance, the kind of boat you have, the kind of fleet you’re racing in, and your level of commitment and expectations. If you want to try to win races rather than simply going out to participate, you’ll need a top-level product.

The choice used to come down to whether you wanted durability or a great shape. Now, thanks to 3Di, it’s more about whether the up-front costs can be justified; quite simply, 3Di sails hold their designed shape for much longer.

The best North 3Di option for club racers is called RAW 360. It is made using polyester, Dyneema and aramid. It’s not cheap but it has a pretty competitive price, given all of the other benefits of 3Di. And of course you get expert advice from our top designers.

What are the best downwind sails for club racing?

There is many options in spinnakers for club racing, starting with the choice between asymmetrical and symmetrical sails (also known as A sails and S sails). For all but the most casual club races, a cruising asymmetric spinnaker tacked to your bow will not make you fully competitive; if you have a centerline bowsprit or pole mounted at the bow, an A sail may work well. If you have a traditional spinnaker pole, you’ll likely do best with an S sail.

If you plan to fly an A sail, you’ll certainly need to discuss the best option with your sailmaker. Shape development in A sails has been dramatic over the last 20 years, and you’ll also want to talk about the best sizes for your sailing area. Do you need an A1, A1.5, and/or A2, and should the sail be tipped toward running deep, be more all-purpose, or be optimized for reaching?

What’s the best spinnaker material?

Even more important for club racing is your choice of spinnaker material. Spinnaker nylons come in two groups, and the first is cruising preg, which has melamine resin in the fibers but is not coated. If you can live with a heavier sail that flies well, this classic .75-ounce nylon is still a very nice, tough material with low porosity. As a bonus, it will still feel good after you drop it overboard once or twice. North Sails NorLon is an example of this cloth; it’s available in three-quarter ounce and one-and-a-half ounce, as well as 2 and 3-plus ounce weights for bigger boat spinnakers.

Compared to NorLon and other classic nylons, the newer, higher-performance nylons have a lighter thread density and therefore lighter weight, but they also have urethane coatings, which stabilize the cloth. Over time, they break down and lose performance.

These higher-performance nylons have pregged fibers plus a surface urethane coating, allowing you to fly a sail with a less dense weave, saving weight without affecting porosity. They have a higher price and break down faster, but you get a sail cloth that weighs 35-40 grams per square meter instead of close to 50.

Bainbridge International’s AirX cloth is one example. It is both pregged and coated and a little nervous in how it flies so it’s less forgiving, but it’s a great cloth for use on boats that sail higher angles downwind. Contender’s SuperKote cloth is also pregged and coated, but is a little softer on bias and more elastic than AirX. This makes it better for boats that reach less and sail deeper angles downwind.

If you only want to buy one spinnaker, you’ll likely want an all-purpose (AP) sail, either asymmetric or symmetric, made with a nylon like NorLon that is pregged but not coated. You can be competitive in many conditions with a sail like this.

If you race in a higher-level fleet, though, you will probably want two spinnakers. The first could be an AP spinnaker for when the breeze is on, made with a good .75-oz material in a nicely shaped sail. The second would be a lighter-weight A or S sail for an advantage in lighter breeze.

Take for example the Melges 32, a fast, modern lightweight boat. If there’s a good breeze we pick the A2, an asymmetrical AP runner. But we choose the A1 for VMG sailing in a dying breeze, because it’s better for sailing more aggressive jibing angles.

We know this is a lot of information, so if you’ve got questions please let us know. You can reach us through online chat, or contact your local loft for more details. We look forward to seeing you next Wednesday night!